Neurofeedback, Global Warming, and the Financial Collapse

by Siegfried Othmer | January 6th, 2010 To someone who has been educated in the sciences it is somewhat jarring to see so many people blithely dismiss the alarming evidence in favor of global warming. And yet when it comes to neurofeedback, we are quite comfortable flying in the face of mainstream thinking and simply dismissing the mainstream position (of skepticism with respect to neurofeedback) as essentially meaningless. In one case, we regard scientific consensus as highly significant; in the other, we hold it in utter contempt. How can one justify both positions simultaneously?

To someone who has been educated in the sciences it is somewhat jarring to see so many people blithely dismiss the alarming evidence in favor of global warming. And yet when it comes to neurofeedback, we are quite comfortable flying in the face of mainstream thinking and simply dismissing the mainstream position (of skepticism with respect to neurofeedback) as essentially meaningless. In one case, we regard scientific consensus as highly significant; in the other, we hold it in utter contempt. How can one justify both positions simultaneously?

The answer lies in the nature of the evidence for both propositions. What makes the case in favor of global warming so persuasive is that it is supported by so many independent lines of evidence, all of which collectively support a model that in turn is also well-supported, namely the key influence of atmospheric CO2 concentrations on global temperatures. Much of this evidence came to exist in the course of research that was unrelated to the issue of global warming. Add to the known influence of CO2 that of many other gaseous effluents, which can be tens to thousands of times worse in terms of their greenhouse effect, and we have ourselves a rather dangerous stew.

For evidence, one needs to look at those changes that average over short-term fluctuations, and one needs to look at regions where the effects are expected to be largest and to show up first: the arctic. Already we know that arctic summer sea ice is running at less than half of what it was half a century ago. Ominous signs of the decay of ice sheets are also seen in the Antarctic. Supporting evidence is then furnished by such findings as arctic flowers blooming earlier, butterflies moving their territories northward in England, and birds advancing the calendar on their nesting behavior. Altered composition of phytoplankton in arctic waters indicates that chemical changes have reached the level of biological significance.

A third line of evidence lies in comparisons between actual changes and those that have been predicted by various climate models (with respect to rise in sea level, change in acidity of ocean waters, alteration of atmospheric and oceanic circulation patterns). We are bumping up against the upper bound of predictions that lead us straight into catastrophe if things are left to take their natural course.

Now when it comes to neurofeedback, matters turn out to be much the same. The proof of efficacy is provided by many independent lines of evidence. Not only are there over a thousand studies attesting to neurofeedback effectiveness by now, but ineluctable evidence is furnished on a daily basis to clinicians doing the work. The clinical evidence just presents itself initially, much like crocuses popping out of the ground in the spring. The evidence is not sought; it is merely observed. (As an example, we have just had the first report of a return of color-vision in person who has been color-blind all his life. This was certainly not the objective of the training.) There is no viable alternative model to explain what actually happens clinically. While there is no way to bring climate into the laboratory, the clinician sees all of human complexity in each client. The result is that many independent lines of evidence may be served by the training of one individual. We do not “treat ADHD.” Rather, we train an individual, and the fallout of that can be global for the person’s functioning. There is no placebo model for that.

Science does not typically progress on the cusp of a truth or falsehood dichotomy. It works on the basis of the best explanatory model that can be brought to bear, and in this case that happens to be the self-regulation model. Neurofeedback training augments the self-regulatory capacities of the organism via feedback on physiological function. No alternative explanation ever proposed comes close.

The difference between our situation and that of climate change is that the neurofeedback skeptics are like the hired guns of the coal industry casting doubt on “An Inconvenient Truth.” They may yell the loudest, and they may appear to speak with one voice, but they are not credible. As for the rest of the mainstream, it is simply not yet paying attention. Neurofeedback is not on their radar screen. It does not appear in their journals. It is not yet part of hallway conversations in academia. The same holds with regard to meteorology. Most mainstream scientists are simply bystanders with respect to the controversy. They are not tracking the issue closely. They trust their colleagues. In the matter of global warming, their colleagues are climate scientists. In the case of neurofeedback, their colleagues are the neurofeedback skeptics. In both cases, the broader scientific mainstream is scientifically inert and hence should carry no weight at all.

Common Issues in Climate Change and Neurofeedback

The basic commonality between the issues of climate change and neurofeedback is the complexity of the phenomenology with which we are engaged. Both the climate systems and the human organism function within a complex self-regulatory framework. In the climate system, a variety of feedback loops is operative, and even though all of them ultimately interact, they are not subject to any kind of central regulation. It is the existence of a hierarchical control system in human bio-regulation that allows us to have such broad, distributed, global effects with neurofeedback. The training is worthwhile, however, only because of one other key distinction: our own regulatory system can learn from experience. So the effects of our exertions in training can be cumulative and long-lasting.

Both systems can be looked at in the perspective of feedback control systems. Both operate within a dynamic zone of stability outside of which the operating conditions are radically altered and substantially unpredictable. This hasn’t been appreciated sufficiently in the discussions about climate change. Given the complexities involved, the best we can do is make some linear projections into the future under the assumption that matters will remain well-behaved. And when scientists are pressed on the issue of how firmly their projections are to be believed, they will tend to get even more conservative in their utterances. Under these conditions, the possible tipping points into major catastrophe are not dealt with, and are not even seriously discussed except at the margins.

The median of projections has been that we might see on the order of 2.8 degrees of global temperature elevation over this century, and consensus is emerging that on the order of 2 degrees of change may be tolerable. However, average Northern hemisphere temperatures differed by no more than about a degree Celsius between the Medieval Climate Anomaly (from 950 — 1200), when Europe was cozy, and the Little Ice Age (1400 — 1700), when it was cold enough to disrupt agriculture in Northern Europe. There is no basis for believing that two degrees of average global temperature change would be benign, or that induced change would be either smooth or uniformly distributed. A number of tipping points could be reached on the way there.

Our climate history is filled with events in which climate change was sudden and precipitous. Evidence is now coming to light that our descent into the Younger Dryas ice age may have occurred over a period of a few months. The idea of precipitous climate change is not new. Back in graduate school during the sixties we were joking about mastodons having been recovered from the Siberian permafrost with buttercups still in their mouths. Rapid climate change indeed!

Slowly changing variables such as atmospheric CO2 may have played a role here as well, but other factors must account for the sudden state transitions. And then positive feedback loops operate to take the system further into extremes. At the moment, we have to be concerned with those feedback loops that build on warming effects and further accelerate them (warming permafrost yielding even more CO2; melting ice changing the earth’s albedo). The danger is that the point may be reached where we cannot readily reverse the trend that we may have ourselves unleashed.

It is the various potential tipping points that truly give climate scientists gray hair. It is because of them that ignorance about our climate future should not be taken as license to do what we want but rather as a caution to be even more concerned about unquantifiable risks. As a society we are doing the equivalent of driving faster after our headlights have burned out and are no longer showing us the upcoming hazards. Environmentally speaking, we are living in an unsustainable bubble economy.

Our own biological regulatory system is similarly subject to catastrophic instabilities: seizures, narcolepsy, catatonia, migraines, panic attacks, rage episodes, asthma attacks, suicidality, extreme mood swings, and coma. Fortunately, even the most severe of them are often self-limiting. With neurofeedback we are now able to enlarge the ‘zone of stability’ in most of these conditions, and even effect recovery from the disregulated state (in migraine, for example, and in bipolar mood swings). Our effectiveness goes far beyond that of pharmacology, and this turns out to be significant for our understanding.

It is not enough to try to stabilize the synaptic junction against seizures with medications. It also helps to interact as we do with the entire regulatory network. That engages the system at the level of complexity at which it actually functions. Seizures represent a collective activity of neuronal assemblies in which they lose their individuality and capacity for independent function and are swept up in a cascade of rhythmic oscillations that eventually pervades all of cortex. We can now enhance the stabilizing capacity of the brain to reduce the likelihood of seizure onset.

The resulting stability is then built in to the system. Once a seizure is unleashed, there is very little to be done at that point. Matters are similar in the climate domain. We have to anticipate the problems. Once a tipping point is reached, we have lost much of our capacity to effect a remedy. And in addressing climate risks, we have to also adopt the network perspective and account for all of the disparate ‘sources’ of the climate problem and to exploit all of the potential interventions at our disposal.

As for seeing the tipping point coming and making very specific predictions as to its kindling, the science is not up to that in any domain. We are not in a position to predict seizures, earthquakes, or climate shifts microscopically. That is traceable back to the complexity of the networks involved, as well as to the intractability of nonlinear interactions. Where predictions have been made, they have erred in the direction of underestimating the risk of catastrophe, and nowhere is this more apparent than in our recent financial history.

The Analogy of Global Finance

In the global financial system we have yet another analogy to both the climate system and to the human brain. The system is complex, and operates by a variety of feedback loops on many levels. Intelligent regulation is ostensibly in play at a number of levels. At some remove, human agency is involved in every transaction, allowing complex decision-making to play a corrective role. What was insufficiently appreciated is that even with the involvement of intelligent supervision the system was capable of going unstable. In fact, human inputs could align unidirectionally to push the system over a cliff, even though that was in no one’s interest—most particularly not of those who did the pushing! The human element that was stabilizing under ordinary circumstances could suddenly become catastrophically destabilizing. Now anyone familiar with the history of finance would not see this as novel. Boom-bust cycles have been the story throughout the history of finance.

The new element at work was econometrics. Markets were yielding more and more to formal analysis. The late Paul Samuelson was a father to the movement. He saw the tiny incremental movements of markets—one transaction at a time—as analogous to Brownian motion of small particles in suspension. If the particles were small enough, they could be seen being jostled by individual energetic molecules bumping into them. The movement of markets is microscopically random around a slowly moving mean. In the day-to-day unfolding of market activity, this assumption worked out pretty well. The model cannot, however, account for collective activity among the ‘particles.’ In the case of Brownian motion, the probability of that is so low as to be discounted. Not, however, when humans are brought onto the scene. Fear can be instantly communicated among the actors and precipitate collective behavior that cannot be accommodated in the models. When all is said and done, the models did not concern themselves with systemic stability, and so here we are—somewhat the wiser and perhaps much the poorer as well.

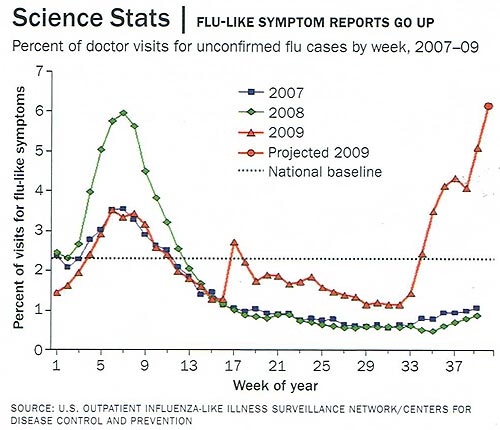

An illustration of collective effects is shown in Figure 1, where reporting rates are given for the flu in each of the last three years. The sudden jump in apparent incidence of H1N1 is due to the publicity given to the outbreak in Mexico, which simply induced more people to seek medical help. (The Figure is from Science News.) Our prevailing financial models assume independence among the constituent events. That is to say, the same distribution holds for every element of the event stream, regardless of the order in which it occurs. When we instead have substantially correlated or collective modes of action, the models are not applicable.

For our purposes, the important aspect here is that in this case ‘mainstream thinking’ went grievously awry. In fact, the existence of a consensus view, supported as it was by arcane mathematical models blessed by Nobel laureates in economics, contributed to the collective misappraisal of risk. The piling up of one academic analysis upon another had the effect of walking the big actors in the financial universe away from reality over time. The reset that was ultimately triggered could never have been microscopically predicted, despite the fact that its occurrence at one point or another was a virtual certainty.

The Financial System and Neurofeedback

Modeling of brain function has been a preoccupation in the EEG field as well. The early impetus was given by E. Roy John, a physicist by training. In all such efforts, we are constrained by having to work with models that are tractable. The downside is that the models then become the working reality in our heads, which is what happened in the realm of finance. All statistical modeling of brain function assumes that EEG behavior is stationary and well-behaved—just as was the case in finance. The data samples that are analyzed occur over short periods of time—just as in the case of financial analysis. Samples that are not well-behaved are omitted from the analyses in both cases. This leaves the rare event, the large excursion that violates the models, out of the discussion. The currently standard models therefore cannot incorporate the brain instabilities that are of primary concern to us clinically…and financially.

The analytical approach to the EEG and the practical approach of the clinician are therefore two largely separate worlds. The same has been true in finance. The arcane theories may have sedated the decision-makers at the top, and they may have empowered the high-paid gunslingers, but they did not fool the trader in the pits—particularly in the futures markets. As Hermann Kahn of the Hudson Institute said long ago (I paraphrase): ‘You can readily persuade the intellectual with a good argument. But you cannot so readily fool the farmer.’

An Overview and Summary

We have seen standard models derived from physics applied to three different complex systems—the climate system, the central nervous system, and the world of global finance—that are all of critical relevance to our continuing well-being. It is also clear to physicists, however, that the existing models cannot reflect the very thing that we should be most concerned with—the likelihood of a major excursion into instability. So it is that physicists are also among the primary critics of the modelers.

Hans Joachim Schellnhuber is the Director of the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research and the chief adviser to the German government on climate matters. He is a physicist with a specialty in chaos theory. He judges the likelihood of a major climate catastrophe at some 30% even under present conditions. The consummate authority on climate matters in the United States is James Hansen, director of NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies. He also received his Ph.D. in physics. He believes that we are already in a danger zone at current CO2 levels, while we are adding CO2 to the atmosphere at a rate 10,000 times larger than natural forces can reduce it. Human corrective intervention is mandatory, and given the time constants involved, it is past urgent.

As for statistical modeling of the EEG, Sue Othmer and I are two people with a physics background who have ongoingly asserted that whatever the merit of conventional QEEG assessments, their connection with brain stability and state regulation is tenuous at best. Further, the predictive power of such data for training protocols is not to be assumed, but must be explicitly proved in rigorous comparative testing. (After all, everything in neurofeedback ‘works’ to some degree.) Ironically, those who beat the drums most loudly for having a ‘science-based’ discipline seem to be the most easily pacified merely by seeing the numbers on the page, without serious investigation of the traceability of those numbers to behavior and its dysfunctions.

In the rather simplistic treatment of the data furnished by routine QEEG analysis, the field imitates the field of finance, with a similar disconnect from the reality in the trading pits and in the clinical office. We should learn the lesson. Benoit Mandelbrot, the father of chaos theory, was once asked why he chose to study finance. His answer was straight-forward: Here was a wealth of data constantly being served up—all suitably quantified for his purposes. Global finance was complex enough to exhibit the features of chaotic systems that he wished to study. The world of finance would illustrate the behavior of chaotic systems just as well as anything else. By the same token, the catastrophic failure of econometric analysis when it mattered most should be a cheap lesson to the EEG model-builders. They are suffering from the identical flaw.

Our own reliance on feedback of the ongoing EEG dynamics at fixed frequencies is yielding results across the board—not only in terms of enhanced brain stability but also in improved homeodynamic regulation. Similarly, Val Brown’s reliance on feedback of major state transitions also effects improved stability of state as well as improved homeodynamic equilibrium. Neither approach orients itself to observed stationary deviations in the EEG. In fact, both head in the opposite direction of giving the brain information only on its instantaneous state trajectory. If we consider the continuum of EEG phenomenology from the stationary properties at one end to the dynamic properties at the other, then the relevance to neurofeedback increases as we approach the dynamic end. These ineluctable facts contradict the cardinal assumptions that underlie traditional QEEG-specified training. And the more a particular nervous system is subject to instabilities, the more irrelevant such assumptions appear to be.

The EEG seemed to present an ideal opportunity to promote a quantitative approach to the study of behavior. But even as the traditional models were being recruited into service, others realized that the brain operated by different rules. This was clear to John von Neumann already in the fifties.The challenge is to explain just how rapidly the brain is capable of appraising information and implementing responses, under conditions in which it also remains unconditionally stable. So the brain has to be organized for rapid shifts in some respects even as it must maintain stability of state in others. The brain must navigate at the edge of stability, and yet remain stable. This is the challenge that confronts us. The existing models will not get us there.

While I do not possess the scientific knowledge about neurofeedback technologies to effectively debate the validity of the claims made in support of these brain-retraining techniques, I do possess enough logical reasoning capability and intelligence debate the controversial issue of Global Warming.

Simply because the ice glaciers at or near the Earth’s poles show signs of melting and decreasing in size does NOT prove that the global (or, average) temperature of Earth’s atmosphere is ever-increasing. What such occurances DO indicate is that the LOCAL temperature in those areas may be increasing. Even IF these local area temps MAY be increasing, other localized areas around the Earth, both on land and over the seas, may simultaneously be DECREASING in temperature!!! If this assumption is correct, and if the areas of decrease in temp over-compensate the areas of increase, we could very well be having Global Cooling instead! Have any of you “scientists” ever considered that possibility???

In my opinion, the only way to prove that the Earth’s average temp is on the increase, is to have an array (lattice-style) of temperature monitoring sensors located around the globe (both on land and at sea) about 20 miles apart. Have all of these sensors communicating their temperature readings by radio wave to a central computer station. Every hour, the synchronized sensors would transmit their readings to this computer system, then the computer would average the readings (totaling the results, then dividing the sum by the number of sensors) and store that average reading for the given hour. This proceedure would be repeated each and every hour for a 24-hour “day”, then another average for the 24-hour period would be calculated by averaging the hourly average values. This would continue for a weekly average, monthly average, yearly average, a decade average, etc. only by following this exact proceedure would you determine whether the Earth is really warming up on a long-term continuous basis.

Even IF the earth has been warming up during the past century or longer, that doesn’t prove that the cause of this change is due to artificial man-made activities. Just normal astronomical issues, such as the relative locations of the nine planets in our solar system, and their effects on solar storm activity, can have a substantial impact on Earth’s weather patterns, and thus global temperatures.

Actually, if we did have a gradual increase in global temp, that may become beneficial to us in the form of being able to grow food in higher lattitudes than were possible last century. This would mean greater crop production that would counter the predicted global food shortages we hear about.

The whole Global Warming FARCE is just a manufactured excuse to place higher fuel taxes on individuals (such as the “Cap-and-Trade” proposal), and place limits and restrictive regulations on human activities and lifestyles by the Global Elite who want to control all of our lives. let us abandone this collective nonsense about global warming once-and-for-all!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

I can only say that if you are reading things like this newsletter, then no doubt your inquisitiveness will in time lead you to accept the reality of global warming. Hopefully policymakers will not wait for you to be persuaded, however. Policymakers rarely have the luxury of certainty. They need to operate on the basis of informed judgment. And prudence at this point would argue for action to forestall the worst of what might happen.

What convinces scientists on the issue of global warming are not isolated data points but rather many independent sources of data that jointly only make sense on the assumption of global warming. As to whether man is causing this problem, that is actually peripheral to the policy question. It is in our interest to counter global warming irrespective of the source of the problem. But it is also quite clear that man’s activities are a significant contributing factor.

Thanks for your thoughts.

Siegfried Othmer