Taming the Heroin Epidemic

by Siegfried Othmer | October 19th, 2016By Siegfried Othmer, PhD

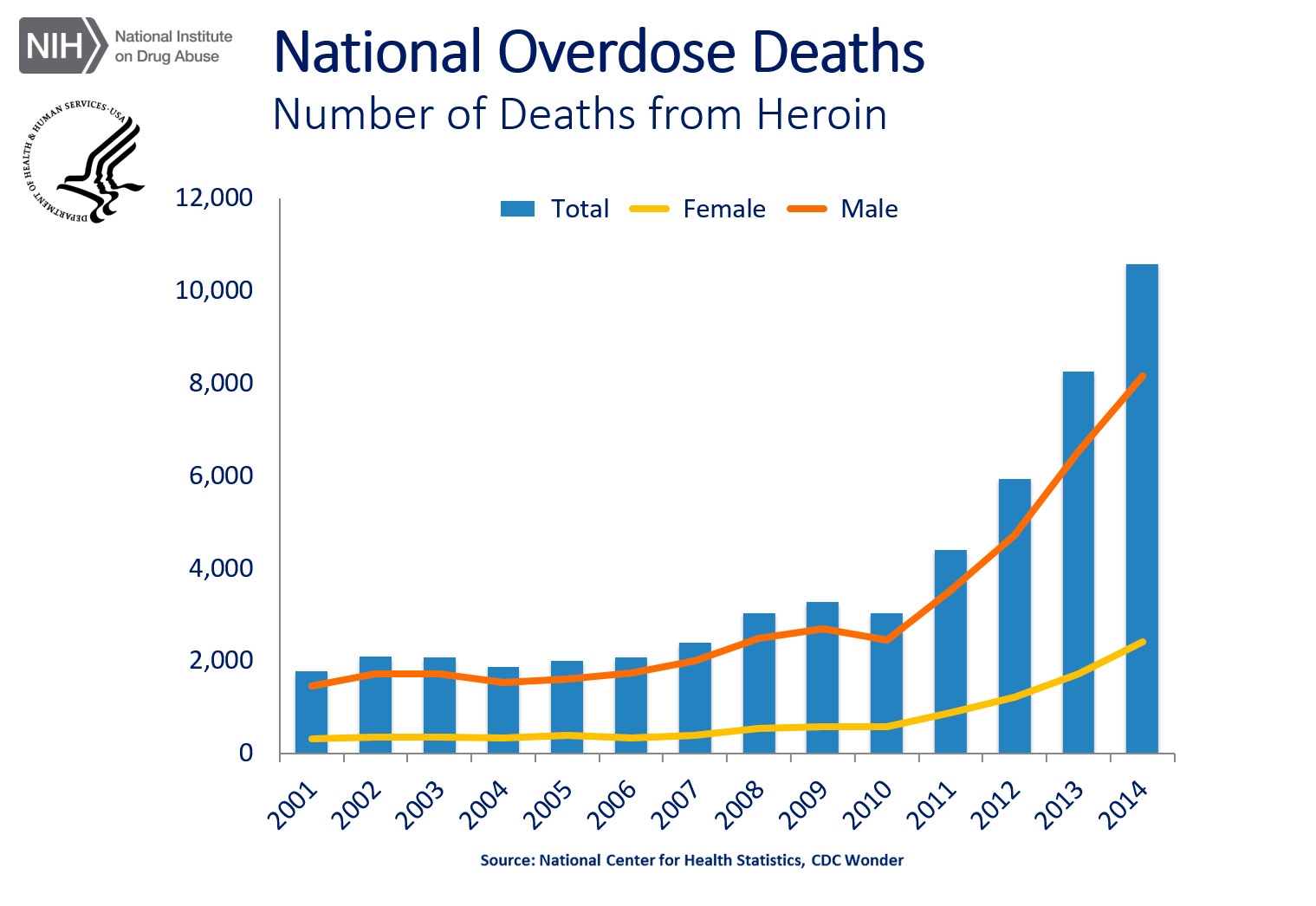

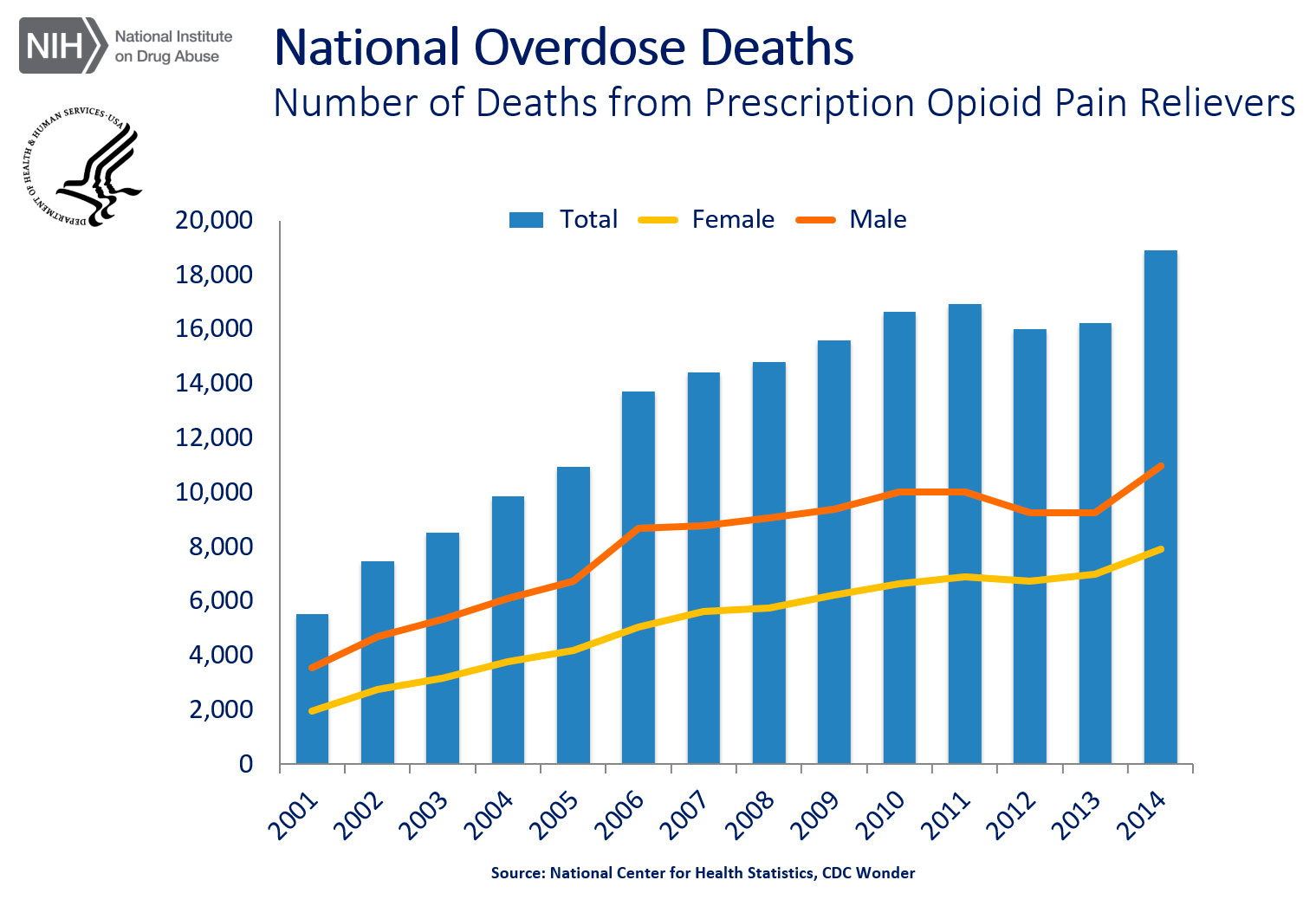

The rapid rise in overdose deaths due to heroin is of frightening dimensions, showing an increase by a factor of six just since 2000. This is shown in Figure 1. Even so, this death rate is eclipsed by the overdose death rate for prescription opioids by nearly a factor of two (see Figure 2). Of course the two trends are closely coupled. It was in response to the overdose from prescription drugs that the campaign was launched to reign in the level of prescribing, and the user population is now finding its refuge in the heroin market.

National Overdose Deaths—Number of Deaths from Heroin. The figure above is a bar chart showing the total number of U.S. overdose deaths involving heroin from 2001 to 2014. The chart is overlayed by a line graph showing the number of deaths by females and males. From 2001 to 2014 there was a 6-fold increase in the total number of deaths.

National Overdose Deaths—Number of Deaths from Prescription Opioid Pain Relievers. The figure above is a bar chart showing the total number of U.S. overdose deaths involving opioid pain relievers from 2001 to 2014. The chart is overlayed by a line graph showing the number of deaths by females and males. From 2001 to 2014 there was a 3.4-fold increase in the total number of deaths.

Instead of heading off the problem of prescription drug overdose we ended up creating a worse problem. But overdose is not just an issue with the opiates. The overdose death rate due to benzodiazepines has also increased by a factor of five since 2000, and at present it overshadows that of heroin (and that of cocaine as well). Yet this has not become a visible issue.

Converging in the current heroin epidemic are two major story lines: 1) the treatment of chronic pain is an outlier within the medical field, and 2) the treatment of addiction is an outlier in the mental health disciplines.

The Treatment of Chronic Pain

The treatment of chronic pain has been controversial within medicine for many years. Pain docs want to treat the pain, but they operate in a societal milieu that is sensitive on the issue of dependency and addiction. For many years, sufficient pain medication was withheld even from cancer patients in their last few months of life because they might become dependent on it.

Eventually the pain docs won out, and post-operative patients were even placed in charge of their own dosing via IV-drip.

But old habits die hard, as illustrated in a case involving a relative of mine years ago. When the patient complained that a fresh boule of morphine drip appeared to be a dud because she hadn’t felt the stuff going into her veins as usual, and she wasn’t feeling the effect either, staff suspicions fell on her rather than on the boule. Was this a case of drug-seeking behavior that needed to be forestalled? The worthy project of putting the patient in charge of the dosing was suddenly dead in its tracks.

If truth be told, dependency is an issue with brain drugs generally. Barbiturates, benzodiazepines, anxiolytics, SSRIs, anti-convulsants, neuroleptics, and anti-psychotics all promote the development of dependency by the very nature of the way the brain works. Over time, it adapts to the presence of the drug(s). In all cases other than the pain meds, however, such dependency is not only accepted, but it is treated as a non-issue. Typically it is not even discussed with patients who are induced to use them.

It appears that the issue of dependency places pain meds in a class by themselves. Why is that? Most likely it is because the issue of tolerance is greater in the case of pain management. The need for pain medication escalates over time because unresolved pain tends to escalate over time. Eventually the dose reaches a level “sufficient to kill a horse,” but of course it doesn’t kill the patient because of the very adaptation that makes such a large dose necessary. Since there is no good end to this story, it should be apparent that a different remedy is called for when acute pain metamorphoses into chronic pain.

The Treatment of Addiction

Addiction seems to be in a class by itself within the mental health disciplines in that the measures used to address it do not comport with the magnitude of the problem. For decades now, addiction treatment has been left in the hands of quasi-professionals. This seems strange for a field in which professionals are quite sensitive on the issue of their prerogatives. Here we have a case of one of the most challenging mental health issues being left to quasi-professionals without serious objection.

Addiction treatment is unique in other ways. When it comes to handling issues of dependency with the brain drugs, the almost universal prescription is to taper the drug, often very slowly indeed. The process can take months. In the case of addiction to heroin, alcohol, and other such drugs, on the other hand, the remedy starts with a detox phase. This can be so disruptive of brain function that we incur a significant risk of seizures in this process. Is that not giving us notice that a big mistake is being made? The brain is intolerant to the rapid change in state. We accept that in all other contexts. Why not here?

Is the ritual of punishment by detox a residue of our historical condemnation of addiction as a moral failing and as a failure of the will? I have been told by those who’ve undergone the process that its severity helps to keep people sober, lest they have to undergo it again! But this is not all. Treatment programs are usually of finite duration of one to three months. This appears to be unique in mental health. Nowhere else is there the expectation that a major mental condition will resolve on schedule and from that time forth remain resolved.

As might be expected, outcomes for such single-shot programs are not good. Once again, a very different kind not remedy is called for.

Why the Conventional Remedies Fail

Neither chronic pain nor treatment-resistant addiction can be treated successfully at the symptom level. One has to go deeper: Why the pain? Why the addiction? What one finds is a high correlation of chronic pain with early childhood adverse events. This correlation is at the 90% level, and most likely it would be closer to 100% if we only knew the actual history.

The result is to put the person on a compromised developmental pathway that renders him or her susceptible to the conversion of acute pain into a chronic pain syndrome. It also renders that person more susceptible to addiction. These two profound clinical challenges find their basis in the disregulation of their neural systems. Resolution lies in the recovery of good regulatory function as a critical element of a therapeutic program.

The Categorical Remedy for Addiction

We will have the categorical remedy for addiction when the affected person is not only able to sustain abstinence but is also free of cravings. Additionally, he must be liberated from any psychic pain, and have gained access to his own core self. This agenda is not trivial, but it is doable, and that’s the good news. These remedies are accessible to any living brain.

The brain’s task of self-regulation is seen as a skill that in these cases requires correction and further development. The method is neurofeedback, which hands the problem off to the brain through the mere furnishing of helpful information on the brain’s regulatory activity in real time. The brain takes it from there. The path of access to the person’s core self is lighted with yet another kind of neurofeedback. Skilled clinicians provide supportive guidance and psychotherapy along the way.

No purgation by detox is required. The training in self-regulation proceeds, and when the brain no longer seeks the drug, usage subsides naturally. The experience of the training is mostly positive throughout, and since this is self-recovery in its most comprehensive scope, the process is also very empowering to the trainee. At some point, the trainee feels himself capable of saying no to the substance categorically, and recovery proceeds the rest of the way.

There is no implication intended here that neurofeedback can be relied upon as the sole treatment modality in the recovery process. But it is our position that no therapeutic alternative presently exists to accomplish the essential mission of restoring functional integrity to the neuronal networks. Likewise it is our position that access to the core self is provided more benignly through neurofeedback than through alternatives such as ayahuasca, holotropic breathwork, EMDR, or other such methods.

The Remedy for Chronic Pain

As is the case with treatment-resistant addiction, chronic pain is a symptom associated with a multi-faceted disregulation status of the brain, and our target for remediation must be that larger pattern of disregulation. In this case, however, a categorical remedy for chronic pain is not presently available.

The best we can hope to do presently is to abort the transition from acute pain to a chronic pain syndrome, and even this remedy must be instituted promptly when the problem is recognized. In cases of chronic pain of long standing, structural changes may well have taken place in peripheral physiology that forestall full recovery.

In these cases, the best that can be done is to rely on the central modulation of pain perception. Clinical experience shows that clients can return to useful and active lives, but objectively appraised, the pain is still there. It just no longer interferes with their lives.

Taming the Heroin Epidemic

We return now to the original topic. As it happens, a significant fraction of the present heroin addiction cohort got there by virtue of a sports injury, or surgery, or even dental surgery. These are cases in point where acute pain converted over time to chronic pain, where neurofeedback should be exceedingly and promptly helpful. Yet others simply found relief in heroin for their own profound disregulation status. They should respond well to neurofeedback, provided it is made available early enough in their addiction history. Chronic dependency takes a lot longer to recover from.

Summary and Conclusion

Clinical resolution of both chronic pain and substance dependency is contingent on the resolution of the underlying disregulation, and neurofeedback is the most effective—and efficient—means toward that end. More specifically, our optimistic appraisal rests on our own clinical experience with infra-low frequency neurofeedback training using Cygnet, which takes us to the foundations of our regulatory hierarchy. Here is where functional disturbances attributable to Adverse Childhood Events (ACEs) must be resolved. We are aware of no efficient alternative.

From a societal perspective, anyone in our society who is burdened by a history of ACEs is unnecessarily compromised in the cognitive and affective domains, as well as with respect to physical health in general. Redressing such disregulation should have been the person’s priority all along—for the sake of his own quality of life and that of his family. This is in the interest of the larger society as well. Seen in that perspective, heroin addiction forcefully calls attention to the existence of a problem that ought to have been recognized and addressed much sooner.

The categorical remedy for chronic pain and of addictions is a preventive one: neurofeedback training in advance of the clinical necessity. Our society would be well served if every child were offered the opportunity to train his or her brain early on, before adverse developmental pathways attain their full scope.

Siegfried Othmer, PhD

drothmer.com

—

Related Article:

Neurofeedback Training for Opiate Addiction: Improvement of Mental Health and Craving [pdf]

by Fateme Dehghani-Arani, Reza Rostami, Hosein Nadali