The Baleful Realities of the Aging Brain

by Siegfried Othmer | April 5th, 2016By Siegfried Othmer, PhD

Years ago an event occurred in Los Angeles that every resident at the time surely remembers. An elderly man plowed through an open-air market in Santa Monica for which a street had been dedicated. There had been no evasive maneuvers, and the man may even have accelerated the vehicle during the encounter. Quite a number of people were killed or injured.

Years ago an event occurred in Los Angeles that every resident at the time surely remembers. An elderly man plowed through an open-air market in Santa Monica for which a street had been dedicated. There had been no evasive maneuvers, and the man may even have accelerated the vehicle during the encounter. Quite a number of people were killed or injured.

The Los Angeles Times reported that when the man emerged from his vehicle he was visibly angry. Angry? How is one to make sense of that. There is only one explanation that has made sense to me over the years, which is that he was angry at himself! He already knew that he was capable of ‘losing it’ episodically, and yet he was also reluctant to just give up the freedom of the wheel. Now he was responsible for the carnage before him, and he was the only one who knew to a certainty that he had been entirely at fault.

Of course my ruminations on this case are speculative, but what we do know to a certainty is that the brain’s progressive failures with aging tend to be episodic. So they are more easily ignored. Just as minor lapses of memory do not crater one’s self-esteem, neither do occasional lapses in mental function cause the elderly to call their mental competence into question. To rely on the driving analogy again, the brain encounters potholes every once in a while. That doesn’t mean one has to stop driving.

The episodic nature of the dysfunction means it is not enough to test for functional capacity every once in a while, as in yet another driving test. Chances are that one would catch the brain in a functional state, which indeed is where it spends most of its time. The problem is that the encounter with potholes, even though rare, can be catastrophic. We really do need to know what the risks are—particularly in the case of elderly folks driving 3,000 pound projectiles down the street.

What is worse is that sometimes the person is even unaware of his state of dysfunction. Consider the following classic anecdote from the recent book “Adapting to Alzheimer’s,” by Sherry Lynn Harris:

Two elderly women, Ollie and Min, were out driving. They could barely see over the dashboard. As Ollie cruised down the street, Min — the woman in the passenger seat — thought to herself, “Hmmm…was that last light red? After a few minutes they came to another intersection, and again Ollie drove right through. Min thought, “I could have sworn we just went through a red light.” She decided to pay very close attention to the next light. Sure enough, the light was definitely red and they went right through. Alarmed, Min said, “Ollie! Did you know we just ran three red lights in a row? You could have killed us.” Ollie turned to her and said, “Oh, am I driving?”

So we know that we cannot always expect to be aware of our own episodic dysfunction. We know this from an experience that is all too common and relevant to us all: When people fall asleep while driving, the brain gives no notice. It just checks out at some point when it is sufficiently fatigued.

With respect to the driving problem, we may in time be bailed out with self-driving cars. But the core problem of episodic failure remains, and recognizing its significance is our first obligation. The second is remediation. Fortunately we have in infra-low frequency neurofeedback an effective measure to improve and to maintain the brain’s overall stability. Perhaps this will only postpone the ultimate decline in brains that are vulnerable to this type of instability. So we also need something along the lines of continuous monitoring of the state of the brain. That is not too far off either, I suspect.

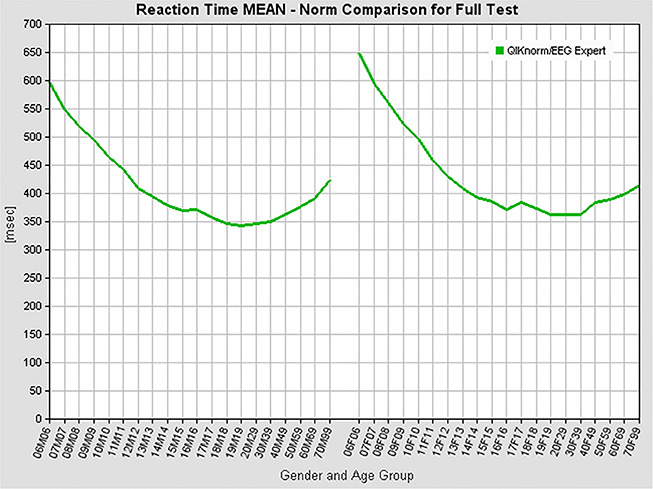

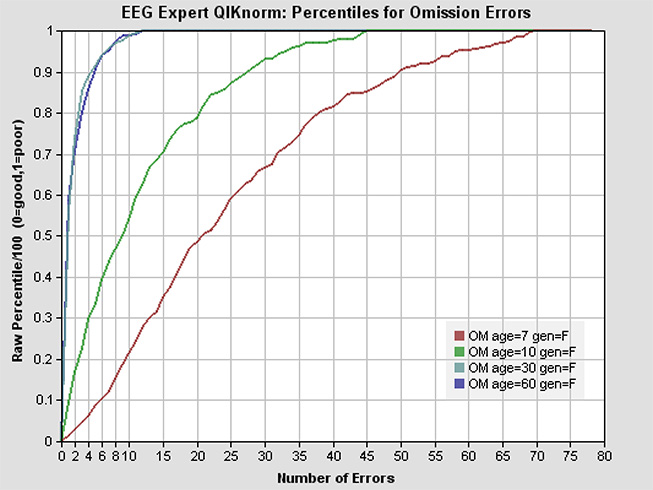

We end this piece on a positive note. When it comes to the state of cognitive function among the elderly, the news are good overall with respect to earlier times (i.e., 30 years ago). Using a continuous performance test as a measure, we find that functional 60-year-old women perform as well as 14-year-olds in terms of choice reaction time (a Go-NoGo test). The curve of mean reaction time as a function of age is shown in Figure 1. Furthermore, they function just as well as 30-year-olds in terms of error rate. This is shown in Figure 2. The cumulative distribution curve for the incidence of omission errors is hardly distinguishable between 60-year-olds and 30-year-olds. So the elderly brain does very well in terms of retaining functional competence. This also means, in turn, that once the performance starts to fall off over time for one reason or another, that will be very noticeable. And just as the QIKtest is good at demonstrating functional competence, it is also good at detecting when people start to fall off the curve.

Mean Reaction Time as a Function of Age, Males and Females

Omission errors, female

Then it remains for us to see about fixing those potholes, and that is where the only demonstrated remedy is infra-low frequency neurofeedback brain training. This is a method with which brain instability is targeted directly, with a dedicated and proven protocol. As our population ages, maintaining brain function will have to be an ever greater preoccupation for these folks, and of greater urgency for our society.

We have just lost William Hamilton, long-term cartoonist at the New Yorker Magazine, to a fatal car crash. It is presumed that he was distracted or fell asleep as he drove through a red light, where his vehicle was struck. He was 76 years old, the age at which driving risk among the elderly starts to exceed that of teenagers. The curve rises quite sharply with age. Even though such comparisons are statistical, they mirror the rapidity with which competence may be lost in the individual case.

An aging anecdote:

“When I die, I want to go peacefully like my Grandfather did, in his sleep — not screaming, like the passengers in his car.” — Jack Handey