National Autism Awareness Month

by Siegfried Othmer | April 30th, 2014 A pril is National Autism Awareness month. So what is new in the field of autism research? A striking finding is the enormous genetic variability we discover upon looking for the genetic causation of the disorder. There are multiple contributing factors, so it is unsurprising that there are many clinical manifestations of the condition. So what we are now calling autism isn’t just what Kanner observed originally, some 70 years ago. But how does such genetic variability arise in such short order? It has been said—correctly—that there is no such thing as a genetically mediated epidemic. The statement is correct in so far as standard Mendelian inheritance is concerned. And yet it is an epidemic that must be explained, and genes are involved.

A pril is National Autism Awareness month. So what is new in the field of autism research? A striking finding is the enormous genetic variability we discover upon looking for the genetic causation of the disorder. There are multiple contributing factors, so it is unsurprising that there are many clinical manifestations of the condition. So what we are now calling autism isn’t just what Kanner observed originally, some 70 years ago. But how does such genetic variability arise in such short order? It has been said—correctly—that there is no such thing as a genetically mediated epidemic. The statement is correct in so far as standard Mendelian inheritance is concerned. And yet it is an epidemic that must be explained, and genes are involved.

We now know that the father’s age at the time of conception is a significant variable in the likelihood of his offspring being found on the autism spectrum. By some mechanism there is a risk to a man’s genetic integrity. This is where the environment comes in, at a minimum, so in fact both sides of the traditional controversy are correct. The causes of autism must be looked for in both environmental factors and genetic vulnerability. The environment we have created for ourselves is putting our collective genetic endowment at risk. Autistic children may be the canaries for our civilization.

Heterogeneity in the causal pathways also calls into question the facile assumption that vaccines have been exonerated as a causative agent. If there are different causal mechanisms, then there is most likely also a differential vulnerability to vaccines. No simple conclusion exonerating vaccines can legitimately be drawn from any of the epidemiological studies that have been done. In any event, no epidemiological study can be used to dismiss an individual case, of which there are now thousands that implicate vaccine-induced injury directly.

On the other hand, on the basis of such studies we do know that vaccines cannot by themselves be the cause of our autism epidemic. Cuba vaccinates its children faithfully, and yet its autism incidence is lower than the US rate by a factor of 300. Something other than vaccines must be involved, and we now realize that vaccines may be implicated indirectly.

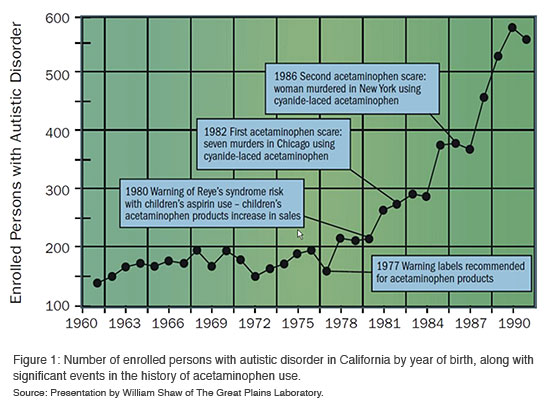

Consider that some twenty years ago it became known that giving infants aspirin placed them at a small risk of Reye’s Syndrome (these claims have since been called into question, but were widely accepted at the time). Parents shifted to relying on acetaminophen when their children showed signs of distress after vaccinations. It is likely that children who respond adversely to a vaccine are evidencing a certain vulnerability not shared with other children. And now it is these very children who are given acetaminophen. If acetaminophen were to be identified as a neurological risk factor in its own right, then these caring parents would have just compounded the problem. That may well be the situation we have been in for the last twenty years, and it could account for much of the growth in autism incidence since the early nineties. (See Figure 1)

We cannot blame it all on any one factor, be it Thimerosal, or mercury in general, or even acetominophen. The heterogeneity of autism suggests that a multiplicity of risk factors is likely involved. But acetominophen may well turn out to be a major factor in the story (Reference 1), or at least a key to the story. Analysis of health data has revealed that autism incidence is strongly correlated with acetaminophen use in various states and countries (Reference 2). In particular, acetaminophen is not commonly provided in Cuba.

It has also been noted that circumcision is commonly followed up with several days of acetaminophen dosing for pain control. Autism incidence is even more strongly correlated with the prevalence of circumcision in different cultures and countries than with acetominophen use directly (Reference 2). This may help to account for the incidence of autism being so strongly male-dominated.

In autism we are dealing with a physiologically grounded disorder, one that calls for physiologically based remedies. However, while we are waiting for the development of better remedies, we also want to do what we can. And what has shown great promise in that regard is neurofeedback—brain training. Our own history of working with autism using neurofeedback goes back more than twenty years. Our early efforts were not rewarded with much success, and we backed off until the condition was better understood. That time has arrived. With our latest methods we are getting much more consistent results, and these are often astounding. A case example:

A few months ago a family came to visit our clinic from the Far East. The family was already very knowledgeable about autism, and they had already undertaken a variety of the common biochemical remedies. They had even known about neurofeedback, and had their child trained with conventional methods for some time. They even went on to rent the equipment in order to continue on a home-training basis. After the child plateaued with the training, they returned the system.

On this particular trip to the States, they had spent three months with a language specialist, with very little to show for their effort in the end. The therapist pronounced sagely that their child exhibited a certain “rigidity of mind.” Or of the brain, as the case may be…

Coming off this experience, the family arrived at our door. The child started to make noticeable progress with every session. Social engagement with the family improved, and the beginnings of language made their appearance. After a couple of weeks of intensive training the parents took a system home with them for continued home training, and within a few weeks we received the report from the family that their therapist had declared, “This child is no longer autistic.” His native brilliance was also starting to show in various ways.

Of course the biochemical remedies had helped to set the table for these gains, but they were not by themselves enough to put matters back on track for this child. At best they eliminated further insults to the brain. They can’t be expected to also undo learned patterns of dysfunction. For that we do neurofeedback.

Is this an isolated case? Well, yes and no. Rarely do we encounter parents who have so diligently done everything they could reasonably do for their autistic child. And that certainly matters. But neurofeedback is capable in principle of helping nearly every child on the spectrum to better function. And it is our growing conviction that infra-low frequency training is the most effective neurofeedback that can be done with these children for the core disregulations at issue in autism. Whereas many therapies being offered for autistic children really work much better for the more high-functioning children, neurofeedback is applicable to all levels of functional deficit.

One of the exciting findings coming out of brain imaging work is that the precursors of autism can be identified very early in the infant’s life—within the first six months. That surely makes the case for early intervention—if only there were something that could be done! Infra-low frequency neurofeedback has been used successfully with an infant of three weeks of age. Hence age is not barrier. As soon as a parent suspects that a child’s developmental pathway is not what it should be, neurofeedback can and should be considered. One does not have to wait for a diagnosis. We are just talking about brain training, after all, and what is involved is nothing more than peak performance training—whatever that may mean for infants. We do not prescribe the outcome. We just provide the infant brain with useful information so that it can sort itself out.

At this point the very best that we can do may be to redirect the developmental pathway in a healthy direction just as soon as we discover that it is not headed there on its own. Of course this holds not only for the autistic spectrum but for a host of conditions that compromise the child’s developmental trajectory. This includes the infant who suffered distress during the birth process from which it has not recovered. It includes infants who are difficult to soothe, who cannot develop good sleep patterns, and who do not develop a healthy relationship to food. It includes infants who may have suffered high fevers, as well as those who react poorly to their vaccinations. In sum, neurofeedback should be considered in cases of all dysfunctions that are not traceable to remediable medical conditions. And because successful treatment of autism has been lackluster at best, autism should be at the top of that list.

Reference 1

Schultz ST, Kloniff-Cohen HS, Wingard DL, Akshjoomoff NA, Macera CA, Ji M (2008). Acetominphen use, measles-mumps-rubella vaccination, and autistic disorder: the results of a parent survey. Autism, 12(3), 293-307.

Reference 2

Bauer AZ and Kniebel D, (2013). Prenatal and perinatal analgesic exposure and autism: an ecological link. Environmental Health, 12, 41.

We now have two well done, prospective cohort studies linking prenatal acetaminophen (Tylenol, paracetamol) use to adverse neurodevelopment. Acetaminophen is the most commonly used pharmaceutical by pregnant women and infants. The first study, by Brandlistuen et al. 2013, found that children exposed to long-term use of acetaminophen during pregnancy had substantially adverse developmental outcomes at 3 years old. These included a 70% increased risk of behavioral problems and motor delays, as well as, double the risk of communication problems. The second study, by Liew et al. 2014, found that 7 year old children whose mothers used acetaminophen during pregnancy were at higher risk of ADHD like behavioral problems and hyperkinetic disorder.