Are We Training Function or Targeting Dysfunction?

by Siegfried Othmer | January 25th, 2016By Siegfried Othmer, PhD

Amajor divide within the field of neurofeedback is the basic question of whether we are aiming to improve function or to expunge dysfunction. This distinction was highlighted crisply many years ago when one of the early researchers, Barry Sterman, said that if he could not identify a deficit in the EEG he would be ethically compelled to send the client home. There would be nothing for him to do.

Amajor divide within the field of neurofeedback is the basic question of whether we are aiming to improve function or to expunge dysfunction. This distinction was highlighted crisply many years ago when one of the early researchers, Barry Sterman, said that if he could not identify a deficit in the EEG he would be ethically compelled to send the client home. There would be nothing for him to do.

On the other side of the debate we have the sharply drawn argument that even if a deficit is being targeted, the brain solves the problem by means of the enhancement of function. It is function that banishes dysfunction, and indeed matters could not be otherwise. We don’t do brain repair. The only answer to bad brain behavior is good brain behavior. So why not target the enhancement of function in the first place? One can think of this in terms of the standard reward/punishment dichotomy. Think about the training of Shamu. The training is based entirely on the encouragement of the desired behavior. The worst that can happen is the withholding of a reward. So it is with training the brain.

We now know that brain function can always be improved. Additionally, we are able to train functions that have no obvious headroom limit: memory, intelligence, fine motor control. Folks do not have to qualify by deficit. This also simplifies the approach. Just as Leo Tolstoy’s unhappy families are each unhappy in their own way, brain dysfunction particularizes in each individual, reflecting both genetics and life history. Function, on the other hand, is organized nearly the same way in all of us. It’s like Leo Tolstoy’s happy families. Fairly standard training protocols take us a long way toward enhancing functional capacity.

We gain benefits in terms of research also. There is no placebo model for extraordinary performance beyond the norm. We do not have to argue about “regression to the mean.” Every individual serves as his own control in the training. We are training with reference to the pre-training baseline in each case.

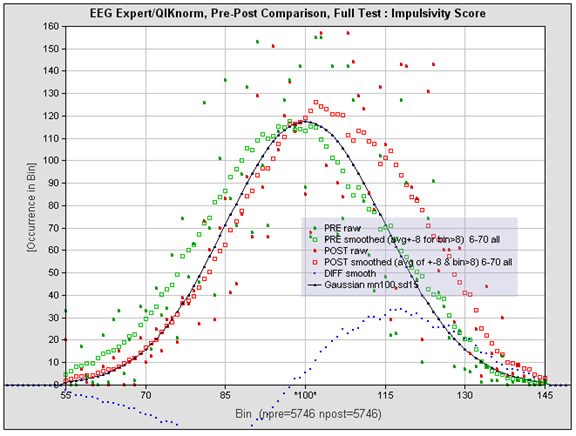

In the accompanying Figure we show the results for an impulsivity measure in some 5,746 individuals who each had nominally twenty sessions of infra-low frequency neurofeedback at the hands of hundreds of clinicians around the world. Yes, that curve represents over 100,000 sessions of infra-low frequency training. Every person so tested (as of 2014) is included in the plot. The black curve shows the normative distribution. The green curve shows the pre-training distribution, and the red curve shows the post-training distribution. Observe that there has been a significant population shift to values above the norm, which goes along with a partial depletion of the deficited population. This plot demonstrates that protocol-guided infra-low frequency neurofeedback is best understood as a training toward optimal brain function. The deficit model falls short.

For further details, see the discussion of this Figure in the full paper.

An absolute joy to read this article. It has addressed some of the criticisms of non linear understanding of function. There is a most disturbing read of this graph, in that, the normative distribution is very closely related to pre training dysfunction presentations. Is this then a valid argument to say that normal is sick? Is the normal population so stressed that they are dysfunctional?

Your concerns are valid. Our reference population is representative of those who walk the earth in many countries. There is indeed a broad distribution of function, and if any of those folks walked into a mental health practice and tested below some established threshold, they would likely be labelled dysfunctional via one or another of the accepted labels. With respect to attentional variables such as impulsivity, the dysfunctional are simply the tail of the “normal” distribution. There is no discrete category; there is no obvious criterion that discriminates the dysfunctional from the functional. The implied concreteness of diagnoses such as ADHD is therefore a convenient fiction. Matters are improved by ascertaining that the person at issue is in the tail of the distribution along several dimensions of behavior, not just one.

We are using population-based norms, but these reflect what is, not what ought to be. So the distribution is not normative in the traditional sense.