UCLA Symposium on Neurofeedback

by Siegfried Othmer | May 5th, 2005Last Friday was the first-ever Symposium on QEEG and Neurofeedback at UCLA under the joint sponsorship of the Psychology, Psychiatry, and Neurology Departments, and of the Brain Research Institute.

Barry Sterman, Professor Emeritus of the Psychiatry Department, started the day off with the comment that it had been 25 years since he last spoke from the podium at the Neuropsychiatric Institute Auditorium. That of course is an indictment of UCLA, not of Barry. That being the case, it is only fitting that the first Symposium of this kind under university sponsorship be held here at UCLA. Barry also had to remind folks that the work he was presenting was by now as much as forty years old. In those early days there were only three laboratories in the country engaged in work with what was called “voluntary controls” that was based on the EEG: Tom Mulholland’s lab in Bedford Mass and Joe Kamiya’s lab at the University of Chicago, and of course his own at UCLA and the Sepulveda VA. Apparently Mulholland’s work was devoted to what is now referred to as the brain-computer interface, in particular using the alpha rhythm to try to communicate, by analogy to Birbaumer’s work with slow cortical potentials.

I learned a couple of things: On this occasion Barry suggested that his own reversal design in the seizure research came before Lubar’s adverse finding with 4-7 Hz up-training, and that he used 6-9Hz as the reward band in the reversal phase as a matter of general precaution.

He also lamented the current trend of no longer looking at the EEG: “The way things are done now you don’t see EEG events, and you should see EEG events.” So Barry is still cueing in on events (e.g. in the SMR band) that are relatively rare in the record.

Said Barry: “I miss these cats.”

Certainly they died in a good cause.

Quantitative EEG Predicts Drug Outcome, Ian Cook

Ian Cook (Psychiatry) reviewed his by now well-known study in which changes in the QEEG could differentiate placebo and medication responders to anti-depressant medication. He uses a measure called cordance, which combines absolute spectral magnitude data with relative spectral magnitude data into a composite measure (a root-mean-square combination).

The most prominent change in cordance is seen early on in the placebo responders, and diminishes after some four weeks. Additionally, placebo responders show a progressive increase in brain activity in frontal region over the duration of the study. Both the medication and the placebo groups increase over the 8 weeks (referring here to the responders only), but the placebo group is the only one that shows significant increase. These changes are distinctly different from those of the medication group. There is both a different time course, and a different endpoint. This is found at the level of group behavior, and does not imply that the measure has high predictive power. It does not.

Cordance changes seen within the first 48 hours also predicted medication response, even though symptom change might not be observable for some days or weeks. Further, data indicate that susceptibility to side effects could be discerned early on in medication trials.

This might be the pathway for drug company interest in QEEG. It was also suggested that the find of QEEG markers of side effects early in treatment speaks against the “allergy model” of drug side effects.

Mechanisms of the Placebo Effect, Andrew Leuchter

Andrew Leuchter’s topic was “Lessons from the Neurophysiology of the Placebo Response.” Leuchter started out with the famous dictum, “One must hasten to adopt the latest medications while they still have a chance to work.” He talked respectfully of the placebo response, saying that first of all it is not an anomalous response in people. Secondly, placebo administration is still commonplace in medicine, as for example in the resort to antibiotics for the common cold. He also warned of the presumption that placebos are harmless. But, all that notwithstanding, it should not be concluded that the placebo effect has any power to “cure illness.”

In the question period, I suggested to Professor Leuchter that his emphasis on the placebo effect depended on the codification of the disease model. In other words, with respect to real disease, the placebo effect represented “the other,” a set of psychologically mediated influences that variously affected one’s sense of well-being. The point is that when we frame matters in terms of “functional medicine”, then that dichotomy is no longer sustainable. It no longer makes sense. I suggested that we are not even claiming to alter disease processes through neurofeedback, and this seemed to surprise him. Up to that point, matters for him had been simple. Since neurofeedback was unlikely to actually effect real change in disease processes, it had to necessarily fall into the bin of some kind of sophisticated placebo response. To hear me assert that we were not even claiming to alter disease processes meant that I was conceding that essential point. Obviously something is missing from the discussion.

Let’s take depression. In view of the findings of Ian Cook and Andrew Leuchter and others with respect to EEG change in placebo responders, one might wonder if there are not multiple pathways out of depression, and that pre-frontal activation is one such pathway that is available to some people. It is not unreasonable to argue that the pre-frontal activation could be initiated by a strong placebo response, and then sustained through further positive reinforcement during the experimental period. And it would not be a huge leap to propose that if the frontal activation were kindled with HEG feedback, or EEG feedback, the same outcome could be achieved.

It is also quite possible that in the disregulated brain there is a kind of random walk quality to frontal activation (much like the stock market), and that those who find themselves in a secular uptrend in frontal activation are those who would later be called placebo responders, if they happen to be under observation in a study at that moment. Depression, as we know, is a largely self-remitting condition in its early stages. It is characteristically episodic.

Leuchter pointed out that to a certain extent the placebo effect is exacerbated in studies. After all, a lot of attention is paid to the subjects. The placebo response often declines after the blind is broken at the end of the study. Of course once the blind is broken the magic of the placebo is no longer operative. But there is also the withdrawal of all that attention to consider. So something must differentiate neurofeedback from classical placebo responding, and that must be the learning of new habits of brain regulation.

Leuchter told of two experiments in which subterfuge was used to evoke a kind of placebo response. A noxious thermal stimulus was used to test the efficacy of an “analgesic cream.” During the initial trial of the magical cream, the level of the thermal stimulus was turned down, thus persuading the subject of its efficacy. During subject tests of the cream at design stimulus levels, the pain severity was indeed assessed as reduced.

Of course we know by now that pain sensation is homeostatically modulated in general. This fact cannot be stretched to cover situations in which we abort migraine pain or other headache pain categorically using neurofeedback. We are not talking about subtle appraisals of pain severity here.

In another such study, subjects were given a joystick to manipulate in case their pain got to be too much to bear. Some subjects indeed ended up believing that they could control the stimulus with the joystick. And of course they were right—even though the joy stick wasn’t connected to anything. This was even confirmed with fMRI scans, which showed less activation when people had a sense of control over their pain.

In the later question period, Sue Othmer suggested that this augmentation of a sense of control was far more relevant to neurofeedback than the overt placebo-inducing “You’ll be able to get rid of your migraines here.” The instruction to the client involves more centrally the idea that the client may expect to exert some control. He or she is not simply the passive victim of the migraine, on the one hand, or the passive victim of the feedback, on the other. “You will be able to tell if things get better or worse, and then we will make an adjustment. You will be telling me which way to go.”

The interesting case of Reboxetine was brought up. It is marketed as an effective anti-depressant in Europe, but it does not appear to work in the USA. The greatest predictor of benefit in anti-depressant administration is the expectation of benefit. Since nobody is beating the drum for Reboxetine in the United States, it also does not work very well. This example was nicely illustrative of the power of expectancy factors. But no doubt a subtext here was that we in neurofeedback were skating forward on the basis of huge positive expectancies, and that of course is not the case. We deal with numerous very tough cases, where families have had their expectations crushed on numerous occasions before they ever came to us. Besides, most of them have to run the gauntlet of mockery by friend, family, and their own doctor to even show up at all.

Finally, it has been shown that expectancy factors influence greatly the response to Deep Brain Implants in Parkinson’s. This has been shown to hold true not only for the overt observable symptoms being addressed but also to autonomic measures such as heart rate. The expectancy effects even register at the cellular level in neuronal firing rates.

The importance of expectancy factors caused Barry to ask later whether the failure to take advantage of known placebo effects should not be considered unethical. Ethical concerns of withholding care had been focused exclusively on the “real” medicine that is delivered for “real” disease. Expunging expectancy factors has not generally been thought to pose an ethical issue regarding the withholding of care. Here is the old dichotomy again.

The Parkinson’s work is particularly illustrative in this regard. No one would argue that expectancy factors account for the entire benefit of the procedure. It is simply multiplicative. I use the term multiplicative here mainly to distinguish it from “additive.” Clearly the expectancy factors potentiate what we consider to be a real treatment. Expectancy gives stimulation more leverage. There is no separable lump in one place that can be studied as the “real” effect of the stimulation and another lump somewhere else that can be studied separately as the subjective “expectancy factor.”

But the use of the term multiplicative also suggests a level of quantifiability that may not be realistic. In practice, the effect of deep brain stimulation is subject to dynamic regulation. As the ads say, prices will vary. Once we have come to recognize that, then it is only a tiny step to realize that perhaps we can just toss out the damned stimulator and approach the whole problem of motor control as one of dynamic regulation involving a number of pathways. Our clinical results in Parkinson’s already match those of deep brain stimulation, and we don’t just have one shot at it. We can change our minds along the way, and try a variety of trainings.

Secondly, we can see the DBS experiments as a paradigm for neurofeedback generally. Our insistence that expectancy factors are too important in neurofeedback to be eliminated without any real penalty to outcome measures does not mean that neurofeedback is reducible to the mere mobilization of positive expectancies. The very attempt to split off expectancy factors is flawed, and therefore an experimental design must be devised that preserves the full potentialities of neurofeedback,

For this reason it is a matter of principle with us that neurofeedback should never be tested under blinded conditions, and we argue that on strictly scientific grounds. The essence of the revolution of mind-body medicine is that some things must be seen whole, and that in particular means behaviorally grounded therapies. The scientific argument is quite sufficient to make our case. That is not to say that there isn’t also a political argument to be made. Curiously, psychologists seem only too anxious to accommodate the MD in the above dissection, even though what would be accomplished thereby is the psychologist’s exit stage right. What would be left is a mere procedure that can then be handled by the MD’s cheap hired help.

But let’s stay with the science side of the argument. In that regard, I want to recall some research being done by Herbert Benson’s outfit in Bedford, Mass, the Mind/Body Medicine Institute. There the placebo effect is being studied, and with great fanfare a role for nitric oxide is being carved out. Benson mentioned this again at his recent AAPB lecture, so apparently they are still enamored of this idea. Now when one’s preoccupation is the Relaxation Response, it is probably a good idea to give the impression that you are not entirely unmoored from molecular biochemistry. So nitric oxide serves as a touchstone, a tie back to the terra firma of neuroscience.

This makes as much sense to me as positing that consciousness resides in the ventricles. The placebo response is not reducible to mere neurochemistry. That’s the equivalent of tying imagery we see on a computer screen to machine language in software. It’s a category error. Knowing that nitric oxide is involved makes us no wiser at all. The question needs to be answered at another level of software, that of the “operating system”, if you will—the brain’s software for state management. And then both the problem and the remedy lie in the same space. The software of state management is capable of being responsive to all kinds of inputs, including in particular our own psychodynamic variables. The solution lies not in separating what cannot be separated, but rather in recognizing what in fact belongs together.

A systems approach to our work is indispensable, and the compartmentalizers will always be out of luck. Neurofeedback is in a scientific sense a “probe” of what is functionally adaptable in our CNS, and we also live on a daily basis with an appreciation that the “state of the system” informs, modulates, or determines the responsiveness of the person training.

The placebo discussion prompted Eran Zaidel to ask whether we might be able to characterize the placebo response physiologically in other ways. After all, placebo responders tend to be more optimistic people; they tend to have better cognitive function; and they tend to have better arousals from sleep. From our perspective, these same observations would be read very differently. A person so described would be seen as being in a better state of self-regulation, which gives him a leg up on recovery. We might also argue that simply using neurofeedback to produce a state of better cognitive function, better sleep regulation, and a more positive emotional ambience might also support recovery.

Independent Component Analysis and EEG Dynamics, Scott Makeig

Scott Makeig spoke on his work with characterizing “Cognitive Event-Related EEG Dynamics.” This, along with Juri Kropotov’s and Eran Zaidel’s presentations, was really the meat and potatoes of the Symposium. (For the newbies in the room, one would have to include Barry’s presentation.) I’m only going to report on some snippets of Scott’s presentation. The dilemma we face is that Brain Dynamics are multi-scale, and every researcher out there believes that their own scale is the relevant one. This is charitably referred to as “scale chauvinism.” Makeig admits that it was not at all obvious that there should even be data observable on the macro-scale at all. Hans Berger certainly worked into an environment where it was believed to a certainty that nothing was there to be found. Now that that threshold has been crossed, what does the macro-scale tell us, and how does it relate to the micro-scale?

In the event, the psychologists went to work on event-related potentials, and the neuroscientists looked at spike histograms at the other end of the scale. The EEG and local field potentials largely got lost in the middle, with only modest application to the identification of organic brain dysfunction in neurology. The two active communities, moreover, had nothing to say to one another. Sooner or later, the “nebulous realm of neural synchronies” and of “spatio-temporal dynamics” needed to be tackled. Here we are handicapped by such things as volume conduction that diminishes our spatial sensitivity. “All local synchrony will project to just about all electrodes,” said Scott. Thus, if the firing of one neuron is irrelevant to brain function, then at the other end of the scale a single scalp electrode is similarly unrevealing.

Such a statement may surprise neurofeedback therapists who are effective in training a single site. But we have to differentiate here that it is only the outside observer that is disadvantaged with a single signal from the brain. The brain is in a position to place the observed signal into context. And that makes all the difference. But even if we take the statement in the sense in which Scott meant it, we know it to be an exaggeration. We can discern an awful lot from one scalp electrode. But it does get us closer to Scott’s contribution here, which is the use of Independent Component Analysis to separate local from distal sources and to exclude artifactual signals. Scott also takes advantage of the fact that the coupling matrix thus developed is reasonably stable, so analyses can proceed with fixed or slowly varying parameters, once these have been determined. This is so much more economical than to strive to do LORETA calculations in real time for feedback applications, as Marco Congedo was trying to do. The EEG may vary rapidly, but not the ICA coupling matrix.

Scott also talked about the fact that the original feed-forward paradigm of vision postulated by Hubel and Wiesel has had to be overhauled. Efferent activity from the visual system in fact exceeds afferent signal streams. We are really looking for things as much as seeing things. We map into an evolving picture of the world that is already formed in our brains. Obviously the same is true for other inputs, such as those to our autonomic receptive regions, the insula, etc. Expectancies are everywhere, right down to the primary sensory modalities.

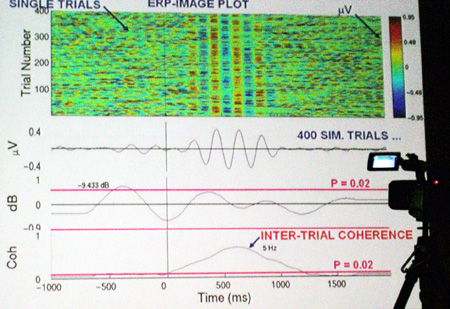

So it is not enough to track visual pathways by monitoring the temporal progression of Event-Related Potentials. In such an analysis, the ongoing EEG is considered to be noise, and gets averaged out. The middle ground is being filled in by people such as Makeig, Pfurtscheller, Klimesch, and Silberstein using techniques of event-related synchronization/desynchronization (ERS/ERD) and event related spectral perturbation (ERSP). Here the EEG remains of paramount interest, so averaging is ruled out. Nevertheless, by displaying data from successive trials in a kind of compressed array, the role of events in phase-locking the EEG can be discerned. This is referred to as Inter-trial Coherence (ITC). Down-stream of the event one also sees consistency of local phase difference between processes, rather than just between process and stimulus.

At the end of his talk, Makeig did us the honor of also mentioning neurofeedback. But he did so by way of raising a caution. He was concerned about the possible effects of over-training. As we know, that is a hazard with athletes, who are at risk of becoming spastic if they over-train! Also, with temperature training we all have to be vigilant that we don’t give people a fever with too much reinforcement on hand temperature!

QEEG, ERP, and Neurofeedback, Juri Kropotov

Juri Kropotov started out by telling us that he started life as a physicist, with a major in quantum mechanics, and that in his current laboratory in St. Petersburg he finds himself only 200 meters from Pavlov’s old laboratory. In Russia, neurofeedback enjoys a certain advantage in that psychostimulants are forbidden to be administered to children for ADHD. Of course he started out as a neurofeedback skeptic. “As a neurophysiologist I thought it ridiculous that a few hours of EEG training could make a difference in ADHD.” He told the story of how such a person could become a believer in neurofeedback. This involved the characterization of some 250 “normal” children in Switzerland as well as of 320 ADHD children through the Institute of the Human Brain in St. Petersburg and some 180 ADHD children in Switzerland.

Go/No-go challenges were used in the assessment. ICA methods were used for artifact correction of eye movement, and for spike detection and removal, in the post-analysis. Wavelet averaging was used for the ERD/ERS measurements, and 100 trials were summed for the ERPs. The Go/No-go challenge was a complicated one. Signals were presented in pairs, each being either a plant or an animal. Only the pairing of two animals was to elicit a response. This is surely the most careful documentation of neurofeedback effects that has ever been done.

Enhancement of the No-Go component of the ERP was found after beta training. Moreover, the ability to raise beta during the training session correlates with cumulative change in ERP. If any such changes had been produced by medication, they would of course have been taken seriously by our critics. As it was, no one at the Symposium panel thought to mention this finding in their discussion later. Here was another clear instance of a neurophysiologically mediated tool obtaining both change in the relevant EEG measures along with corresponding behavioral change.

Cortical Connectivity and EEG, William Hudspeth

William Hudspeth talked about his evolution of connectivity calculations. He showed cases in which he had blindly identified and characterized coup-contracoup injuries from the connectivity maps alone. All well and good, but he stopped short of presenting any post-neurofeedback data. He dwelt on the hyper-connectivity region in such injuries as being of clinical significance along with the more obvious relative isolation seen near the point of impact. The latter has been the traditional preoccupation.

Commenting on the strategy of training connectivity explicitly between sites, Hudspeth suggested that in the case of clustering of sites (hyperconnectivity) he would put all those electrodes together.

In questions, the shortcoming of linked-ear electrodes was brought up, in view of the problem of contaminated references. The active reference problem has been dealt with in the field by varying the analysis for different references…

Quantitative EEG Profiles as EEG Phenotypes, Jack Johnstone

Jack Johnstone talked about “QEEG as phenotype”

His points:

Major neurobehavioral disorders are best diagnosed behaviorally…

You don’t use the EEG as a diagnostic…

The same behavior can have many underlying patterns in neurophysiological profiles

The pattern gives us a guide to therapeutic intervention

The objective here is to search for biomarkers… not for diagnosis but for intervention

EEG and ERP intermediate phenotypes have already been identified in alcohol and anxiety disorders.

The model is not intended to apply to acquired brain injury

A finite number of anomalous patterns are seen in all EEGs:

Candidate Phenotypes:

Diffuse slow waves

Focused abnormality, not epileptiform

Mixed fast and slow

Fontal lobe disturbances

Frontal asymmetries

Excess temporal lobe alpha

Epileptiform

Faster alpha variants

Spindling excessive beta

Generally low magnitude EEG

Persistent alpha with eyes open (hyperrhythmia)

Hemispheric Validation Studies of Neurofeedback, Eran Zaidel

Zaidel: “We know that biofeedback works.”

That is to say, changing specific bands in specific sites results in correlated cognitive changes. “All other conditions are equal between C3 and C4, so if the results with C3 and C4 are different, then neurofeedback works.” Spoken like a true scientist. We are not talking efficacy for ADHD here. We are not worrying about placebo controls. We are tracing observable differential consequences of specific trainings. QED.

This was documented in some Israeli children by Anat Barnea, using SMR enhancement training at C3 and C4, concurrent with theta inhibition over twenty 30-minute sessions. Specific changes were observed in Mike Posner’s Lateralized Attention Network Test, even though no changes were observed in the IVA. Posner is parsing the attention process into an orienting, an alerting, and a conflict-resolving component. With the training, there is a reduction in orienting and conflict-resolving components, and an increase in alerting, as would be hoped.

NF shows hints of site-specificity. It tends to normalize attention networks in both hemispheres. But things are not as separable as first thought. It appears as if NF activates a meta-circuit that involves both hemispheres. Our interest is served if the experiments regarding site-specificity simply open the door for us. Site specificity does not appear to be the story of neurofeedback. It’s much more about the meta-circuits.

The day was closed out with a panel discussion of UCLA experts from various departments, plus a final presentation by Harold Burke, Chief Scientist of EEG Spectrum International.

Robert Bilder (neuropsychology) suggested that a Phenomics enterprise may now be in order to complement the Genomics effort.

Someone said that a quarter of all medical dollars are directed toward functional disorders where localized disturbances cannot be found. These conditions are characterized by high levels of comorbidities: PTSD; IBS, etc. And they have commonalities in terms of EEG phenomena: Early evoked responses are about double in amplitude. He was referring to the P50 component observed with two pulses closely spaced. Schizophrenics and their relatives don’t habituate like normals. Nobody mentioned Rodolfo Llinas’ thalamocortical dysrhythmias as a potential common ground.

Marc Newer (neurology): The EEG is rather non-specific in what it can tell us. We have a fairly limited repertoire of indications that are known to be signs of pathology. The EEG reveals slowing only for fairly gross lesions. Abnormalities could be due to a variety of sources. We should be able to mine more of the data. “We’re still using what people described in the thirties as the principal ways of describing the EEGs. Leaving behind historical baggage allows us to move better into the future.”

James McCracken (Child Psychiatry): “There is nothing more heritable than the DSM criteria themselves.” Better subgroups are needed. He asked the question, “Is there even a need for yet another therapy for ADHD?” After all, stimulants are a home run. When all was said and done, he answered in the affirmative. The eleven children who have died from exposure to Ritalin in this country did not obviously factor into his calculations. That is the observation that first brought Dennis Cantwell to our door years ago, inquiring about the possibility of doing joint work. He said: “ADHD is a bad thing. But you don’t die from it, so you should not die from the remedy.” After Cantwell’s death, there was an initial initiative by McCracken to pursue the work with the NIH, but that was snuffed out pretty quickly. He is too young in his career to be taking chances like that.

McCracken was concerned about effect size in NF. He said that the effect sizes are close to unity for stimulants, versus about 0.5 for anti-depressants. He thought this would pose problems in research. He mentioned that after psychiatry finally recognized childhood depression in the mid-eighties, they simply assumed that anti-depressants would work, and subsequently convinced themselves that they were working. Then twelve successive studies found the tricyclics not to be better than placebo. This was obviously intended as an object lesson for us in neurofeedback. He chose not to mention that things look hardly any better for the SSRIs, with only a single study showing results marginally better than placebo. And then of course there are all those suicides….

This recitation on his part illustrates a central aspect of the medical mindset we are confronting. “They” are under the impression that somehow neurofeedback must be less effective than stimulants, and therefore harder to prove out. That of course is not the case, as the recent Rossiter study has once again confirmed.

Then there is the matter of cost-effectiveness. He estimated the cost of psychostimulants at $1000 per year. In my book, that means we compete pretty well. Then he mentioned side effects. We must have some somewhere. We need at least a few to help our credibility. There’s nothing like a side effect to make things real. Side effects also mobilize the placebo effect nicely.

Mark Cohen (neuroimaging) was the goat of the whole affair. He appeared to wear his ignorance about neurofeedback as a badge of honor. “I would not put this on my head because I don’t feel comfortable.” And for my part, I think we should not partner with anyone for research who would hesitate to try it.

Commentary

Mark Cohen spoke near the end of the day, and left a bad taste in people’s mouths. I’m sure he relished our discomfort. I delight in his irrelevance. I drew a very sobering lesson from this Symposium, which is that these people know a thousand and one ways to screw this up. Part of me is sorry that the dragon is being awakened. They are just not ready for what is about to hit them. Their offer to help with research is a bit like Bush helping Social Security, or Bolton helping the United Nations agenda.

The whole day I had many occasions to be reminded that both Science and Medicine have aspects of a secular religion in our society. And it is just amazing how much they have both adopted from our Judaeo-Christian heritage. There is the emphasis on Scripture, first of all. There is the emphasis on doctrinal integrity, and of doctrinal homogeneity. (All the essential disagreements are marginalized.) There are the sanctuaries and the surplices. There is, finally, the priesthood and the theology faculty. And it is simply not ok for the faculty to ever have its theology informed by the unwashed laity. We were in the presence of the theology faculty at the Divinity School of Modern Medicine. It was necessary to be clear about our place in the scheme of things, and it was left to the last UCLA speaker, Mark Cohen, to do the dirty work.

So, given such mindsets, is it better to have these people in the boat, or would it be better to leave them as adversaries? We have no choice about their adversarial posture, but we do have a choice about collaboration. I suspect that collaboration would be just an endless and ultimately fruitless enterprise. The analogy is to the cowbird in the United States and the cuckoo in Europe. As soon as the egg hatches, the siblings will find themselves expiring on the forest floor. These people carry their intellectual hegemony with them wherever they go.

The whole day Jack Johnstone was reminding speakers to make disclosure of their financial ties. No one on the panel saw fit to do so. Drug company money it to these people as water is to fish. That makes disclosure a merely frivolous exercise. I don’t see this mindset as fundamentally alterable with this generation of senior scientists. We find ourselves in a position somewhat like 1964, when plate tectonics finally dawned on geology, and when lithium was finally accepted in the United States for manic-depressive illness. We are witnessing an impending watershed in man’s understanding of himself.

What neurofeedback involves is not, after all, a matter of simply adopting a new technique. Rather, it is to refashion the entire enterprise of providing health care around a self-care model. This involves a significant devolution of power. Such changes are rarely adopted rationally from the inside. Rather, they are imposed by developments in the society at large. A similar dilemma confronted Freeman Dyson with respect to the Viet Nam War. Said he (approximately): “You cannot influence the system from the outside; and on the inside your views simply get absorbed and neutered.” Eventually it was outside influence that turned things around. He could not do it. The society at large could.

Let us be about the business of making people well. The first overture should be theirs. They should come to our offices and ask, “just what is it that you do”? They will tell us when they are ready. After all, that’s what Dennis Cantwell did.

P.S. It has never ceased to amaze me that in my 20-year basic (neurobiology) and clinical (sleep medicine) scientific career the most closed-minded people on the planet are scientists! Ed O’Malley, MD –And no one more so than a scientist whose paradigm is threatened.

This entry was posted on Thursday, May 5th, 2005 at 7:32 pm and is filed under Uncategorized. You can follow any responses to this entry through the RSS 2.0 feed. You can leave a response, or trackback from your own site.