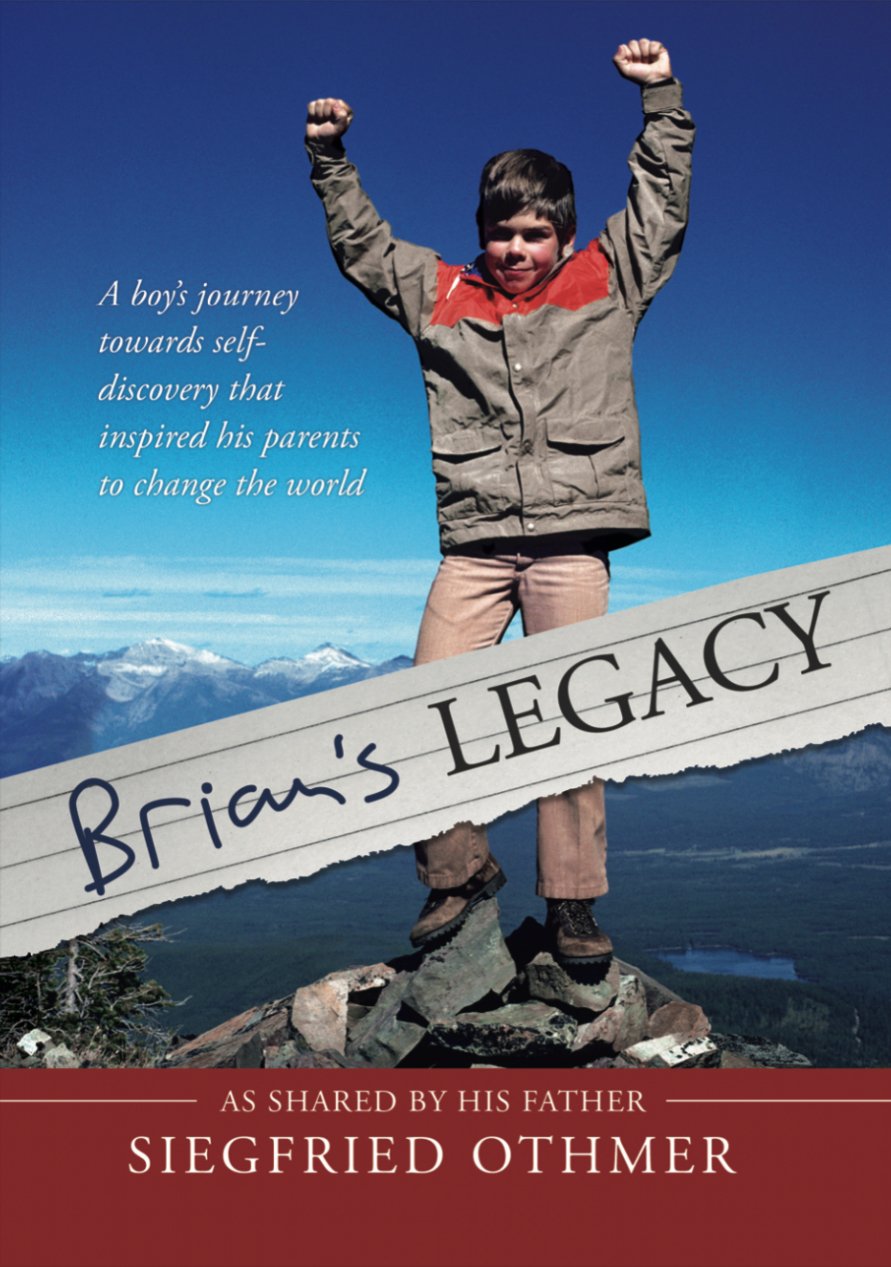

On the Life of Brian Othmer

by Siegfried Othmer | August 23rd, 2024

For many early neurofeedback professionals, the impetus to enter this field came through a compelling personal experience either with their personal training, that of a family member, or that of a client. And thus it was with us as well. In fact, our first encounter with neurofeedback through our son Brian remains a standout success even in the context of the subsequent third of a century of often ground-breaking clinical experience.

Brian started exhibiting behavioral oddities quite early in his life, and over the years these became more troublesome—and more mysterious. When it eventually came to violent episodes that seemed entirely unprovoked, my wife Sue and I were terrified. In our perspective, these fights looked utterly intentional, but then Brian always became profoundly remorseful in later reflection on the event. He had clearly not been in control of what was happening. There were problems at school as well, and at the age of eight, at the beginning of third grade, Brian was expelled from Roscomare Road school in Bel Air, Los Angeles. School officials held us entirely responsible for his misbehaviors, duly recited back to us item by item. We too saw this as somehow our own failing, as we had only the parenting model to go on.

“Brian, you have to learn to control your behavior!”

“I don’t know, mom. I guess I am just an evil person. I guess I am just going to go to prison when I grow up.” OK, let’s start this conversation over again….

“If prison isn’t for people like me, who is it for?” In our desperation, we had placed Brian in a terrible bind. We had burdened him with the imperative to control his behavior, which he already knew to be quite impossible.

Fortunately, our pediatrician Robert Marshall considered the possibility of a neurological involvement and placed Brian on a low dose of Dilantin. Brian reacted positively, and soon thereafter he was placed on the new drug Tegretol, still experimental at the time. We saw light at the end of the tunnel, and it came time to see a neurologist. The famous John Menkes first dismissed the notion of sub-clinical seizure activity being responsible for the behavior, the model in which we had become invested. Once he saw that the Tegretol blood level was within the therapeutic range, however, he changed his view. With the combination of Dilantin and Tegretol, overt seizure-like activity was now largely controlled. But all was not well; there was still a propensity toward episodic rage.

The diagnosis of epilepsy had the perverse effect of focusing attention rather exclusively on that issue, which then allowed other equally serious problems to pass beneath notice. There were also the side effects of the drugs, which included considerable cognitive dulling, that simply had to be endured. And Brian was no longer the hero in T-ball. Brian submitted to the drug regimen faithfully but reluctantly.

If our young son Brian were referred to a psychologist or child psychiatrist in the present day, he could undoubtedly also be diagnosed with Asperger’s, Tourette Syndrome, pediatric Bipolar Disorder, depression with suicidal tendencies, and of course, for good measure, ADD. A meticulous diagnostician might also have identified Intermittent Explosive Disorder. Brian often had paranoid episodes, and these were typically accompanied by unusual somatic complaints, such as the sensation that one half of his body was warmer than the other half. Prior to the introduction of anti-seizure medication, he also had night terrors and episodes of sleepwalking. These symptoms could not be understood in a psychological frame. A psychophysiological model was needed.

At the time (over forty years ago), there was essentially no awareness within the professional communities of Asperger’s or of pediatric Bipolar Disorder, and very little acquaintance with Tourette Syndrome. Even if there had been, remedies would have been scarce. These were the days of Haldol and Orap as the sole remedies for Tourette’s, and of lithium for Bipolar Disorder. The essence of Brian’s problem would have been missed. In our current perspective, the most appropriate description would have been that Brian was suffering from developmental trauma by virtue of his affliction. He could not relate well to other people. Essentially no human interaction was for him an entirely positive experience, including interactions with us, his parents. He was living within a bewildering mental universe in which interactions with other human beings were inscrutable, and thus experienced as inconsistent, unreliable, and unsafe. At times Brian must have been living in a kind of Kafkaesque terror.

A modern framing would recognize much of this as a kind of attachment problem. This was not the usual kind of attachment disorder, however, that is rooted in child abuse and neglect. We were trying to do our best by him, and he was never physically punished. That was an iron law in our household by virtue of my own experience with the ‘black pedagogy’ of German parenting. This attachment issue was entirely neurologically driven, at least at the outset. Brian’s unreliable brain did not allow for the formation of stable and rewarding attachment bonds. His brain may have made only occasional excursions into overt seizures, but the underlying disturbances were an abiding, essentially continuous, presence in his brain.

On top of everything else, Brian’s baby sister Karen, who arrived when Brian was five years old, developed a brain tumor early in life. As dutiful parents, we were persuaded to pursue every medical option that was offered to us, which meant that our parental energies and resources were substantially committed to Karen’s care. Brian was obviously resentful, and no doubt wished his sister out of his life. When his sister died at the age of fourteen months, Brian surely felt responsible. He was already persuaded that he was a bad person that really did not belong in this world, and his intimation that he had evil powers just confirmed it. Yet he could not share his thoughts with us, for obvious reasons. He carried this burden with him and later even became suicidal.

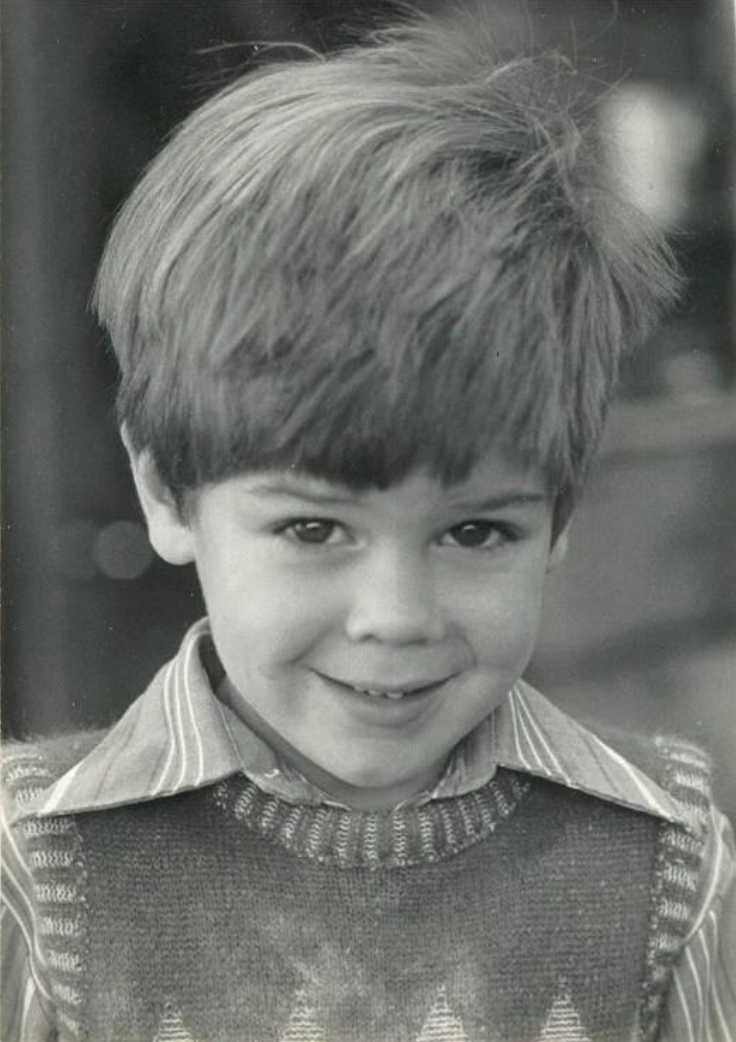

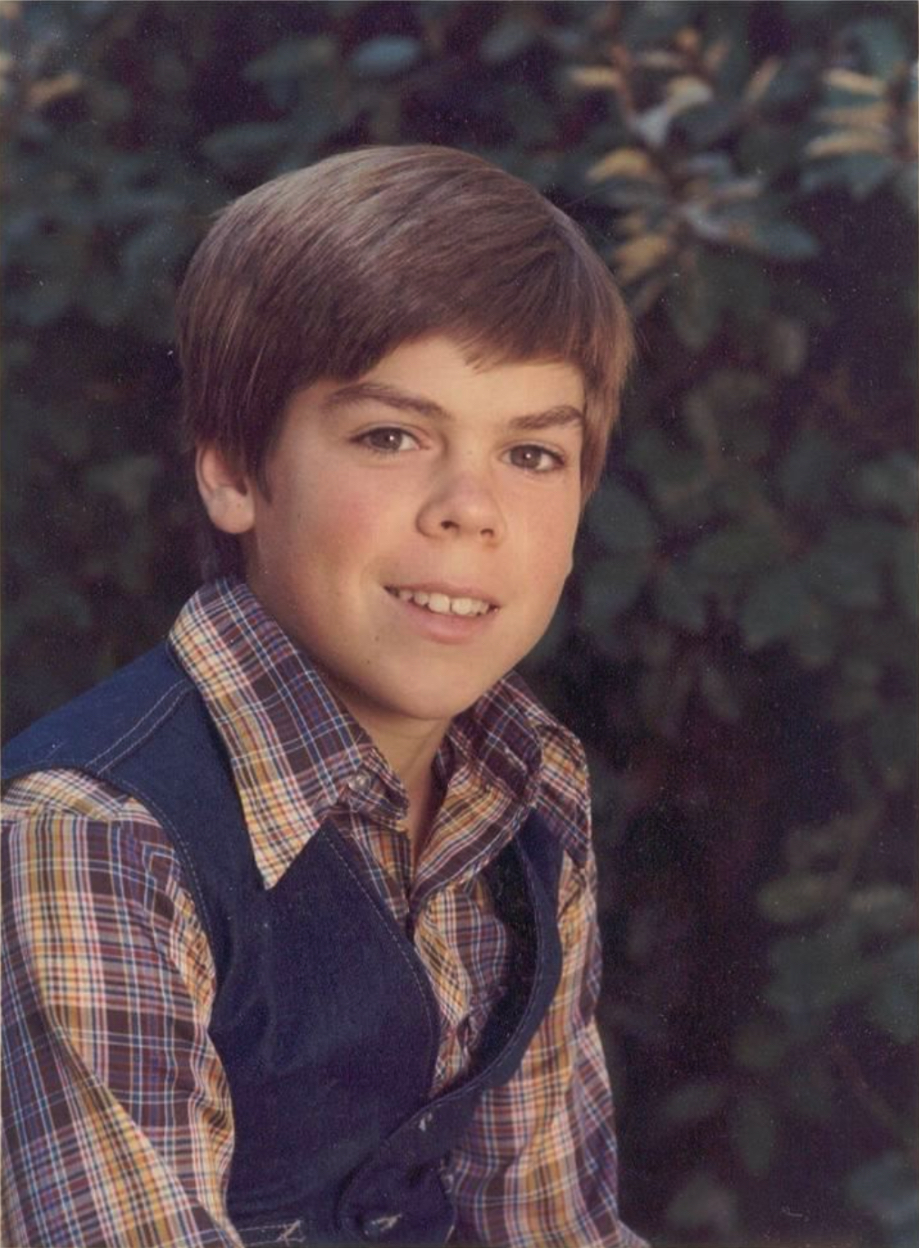

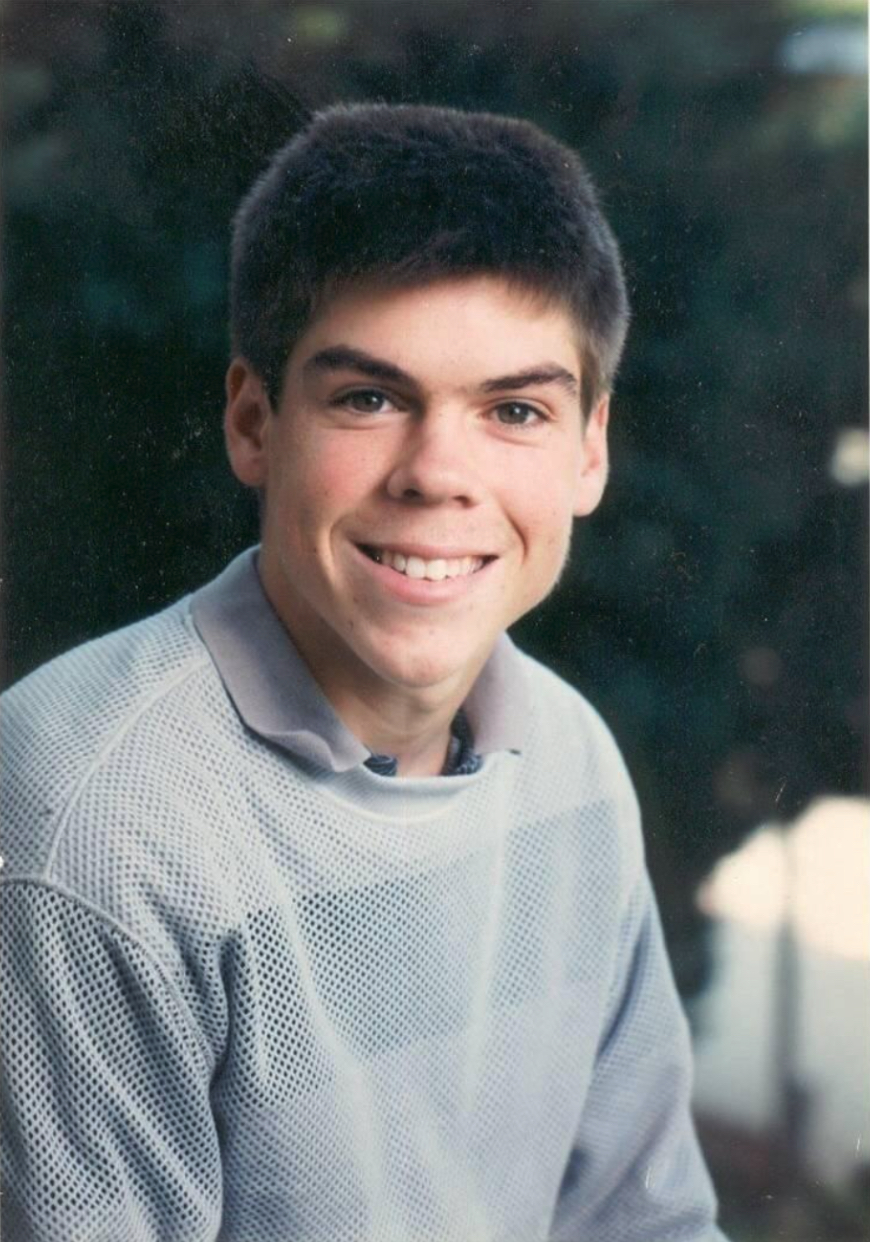

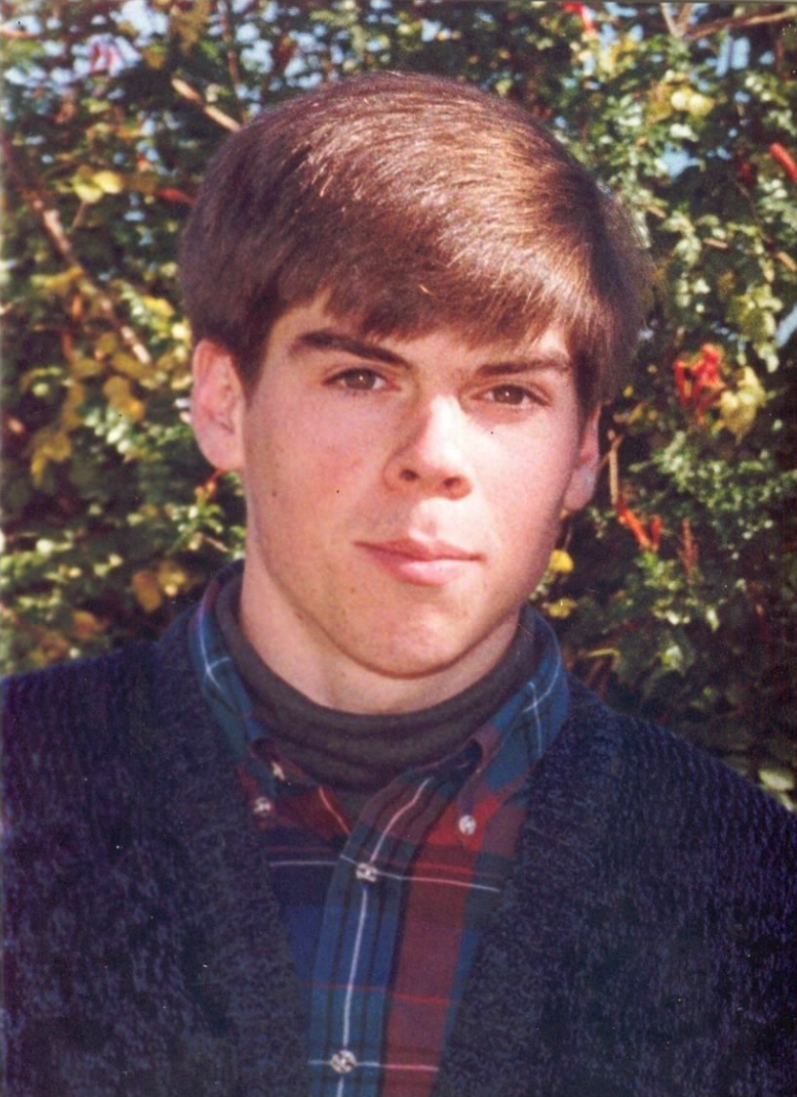

Just as Brian was a mystery to us, his parents, he was also a mystery to himself. But at least we had a lifetime of experience to go on and professionals to rely upon. Brian, on the other hand, had no safe harbor from which to survey his own condition, and no stable basis to anchor the construction of a positive self-image. Remarkably, in all this turmoil he did become persuaded that there was a core self that was both intact and essentially good. With the gift of a kind of inner wisdom, he decided at one point that he was not to be identified with his behavior. He was simply not the person others got to see. After all, his true self did not wish to act that way. It was the recognition of his essential goodness that ultimately carried him through. In first instance, this put an end to his ruminations about suicide. Brian’s wholesome core self is reflected in all of the images, none of which give even a hint of the problematic child that I am describing.

Just as Brian was a mystery to us, his parents, he was also a mystery to himself. But at least we had a lifetime of experience to go on and professionals to rely upon. Brian, on the other hand, had no safe harbor from which to survey his own condition, and no stable basis to anchor the construction of a positive self-image. Remarkably, in all this turmoil he did become persuaded that there was a core self that was both intact and essentially good. With the gift of a kind of inner wisdom, he decided at one point that he was not to be identified with his behavior. He was simply not the person others got to see. After all, his true self did not wish to act that way. It was the recognition of his essential goodness that ultimately carried him through. In first instance, this put an end to his ruminations about suicide. Brian’s wholesome core self is reflected in all of the images, none of which give even a hint of the problematic child that I am describing.

In its daily particulars, however, life was hell. It was a special hell for his brother Kurt, some seven years younger. He had been born to us to fill the chasm left in our lives by the death of Karen. Into this living hell, we now introduce neurofeedback. Brian is seventeen years old, having been on medications for some nine years. He is in eleventh grade in the local Waldorf school, Highland Hall in Northridge, and we regard his life beyond High School with some foreboding. Is there really an alternative to institutionalization, given the unpredictability of his behavior and the non-negligible risk of a descent into violent behavior?

The neurofeedback practitioner was only a few miles away in Beverly Hills. Sue, with her academic background in neurophysiology from Cornell, was intrigued. The technique made sense, and we were inclined to give anything with some promise a shot. This is not to say that we were pushovers for anything that came along. On the contrary, one is hardened by all the failures and false starts one encounters along the way. It’s just that parents trust their ability to judge if their child is truly being helped. The initial buy-in is only provisional.

It was about a month of training sessions at a rate of two per week that led to the first observation by an outside observer to the effect that “Brian seems different. He is calmer. Are you guys doing anything?” We now had independent confirmation of what we ourselves had been observing. And this was just the beginning. The fights with Kurt eased off. It was no longer ‘Kirt is dirt.’ Brian started making eye contact; he was starting to make friends at school; he hung out in the kitchen after school to converse at length with his mother. He was almost giddy with the realization that interaction with other people could be an entirely positive experience. He now had to recapitulate his lost childhood and adolescence.

It was about a month of training sessions at a rate of two per week that led to the first observation by an outside observer to the effect that “Brian seems different. He is calmer. Are you guys doing anything?” We now had independent confirmation of what we ourselves had been observing. And this was just the beginning. The fights with Kurt eased off. It was no longer ‘Kirt is dirt.’ Brian started making eye contact; he was starting to make friends at school; he hung out in the kitchen after school to converse at length with his mother. He was almost giddy with the realization that interaction with other people could be an entirely positive experience. He now had to recapitulate his lost childhood and adolescence.

The following year Brian got himself into college, and ultimately had a very successful college career. He majored in computer science, and even developed the first feedback games for our computer-based neurofeedback system—Pacman and Boxes—on an Amiga. At one point, Brian took time off to attend an Outdoor Leadership School experience involving mountaineering excursions in Colorado. Upon his return to college, he had to take what was available in terms of student housing. On visiting him at Cal Poly Pomona after his return, we found to our horror that Brian had had to move in with an unsavory roommate in the dorm. We never met the fellow, but it was not promising that the only thing in his room with words written on it was the menu of a local pizza parlor. We suspected that anyone who was still living alone by spring probably ought to remain living alone. Brian soon confirmed our fears.

This roommate had been trying to provoke Brian into seizure at night by repeatedly flashing the room lights on and off, calling on the phone, making a racket, and other shenanigans. Brian related all this to us matter-of-factly. He had been suffering all these indignities for some time now without protest. Sue was horrified. It was clear that Brian was reacting to his abuser in the classic manner of an abused child. He had accepted his status of victimhood.

It became clear to us that Brian’s early experience of life was effectively that of an abused child. Even our parenting, although always well-meaning, was to an extent a part of the world that did not make sense to him, and was therefore seen as threatening and of ambiguous portent. This confronted us starkly with the devastating impact on Brian of our early fealty to the behavioral model, as only he was aware of his own utter inability to control his own actions. We now have feedback techniques that can delve down into these deeper regions of the core self and resolve even the consequences of such early traumas.

In his senior year, Brian resided in a shared living arrangement with some classmates. Brian still had his susceptibility to seizures, and he was still on a very low level of medication, namely about 125mg per day of Tegretol. Most neurologists would not regard that as a medically effective dose, but Brian could not even take that small amount in one dose. He had to spread it out over the day. As often happens, the neurofeedback had made him much more sensitive to the medication.

The low level of anti-convulsants allowed Brian to function without compromise to his cognitive skills. But it also rendered him more vulnerable to dietary factors to which he was sensitive—chocolate and all manner of spices (which are nervous system stimulants, after all). Just a few months short of his graduation, Brian succumbed to a nocturnal seizure that we surmise must have been due to some spices he ate at the college cafeteria, perhaps some paprika or allspice or MSG. It was early March, 1991, just at the time that our armed forces were triumphant in Iraq and Kuwait. We were untouched by all the honking and flag-waving. At that moment, we could only identify with the many tens of thousands of Iraqi mothers whose sons would not be returning home either. It had been six years to the day since Brian had his first session of neurofeedback.

The low level of anti-convulsants allowed Brian to function without compromise to his cognitive skills. But it also rendered him more vulnerable to dietary factors to which he was sensitive—chocolate and all manner of spices (which are nervous system stimulants, after all). Just a few months short of his graduation, Brian succumbed to a nocturnal seizure that we surmise must have been due to some spices he ate at the college cafeteria, perhaps some paprika or allspice or MSG. It was early March, 1991, just at the time that our armed forces were triumphant in Iraq and Kuwait. We were untouched by all the honking and flag-waving. At that moment, we could only identify with the many tens of thousands of Iraqi mothers whose sons would not be returning home either. It had been six years to the day since Brian had his first session of neurofeedback.

We had lost not only a son but a likely life partner in our neurofeedback work going forward. Brian had already bitten into this project with great determination and fervor. With his death, our commitment to pursue this work was only reinforced. Inevitably, our thoughts frequently go back to that time, and also inevitably, one tries to repair history. What if we had known then what we know now? Our modern approach to seizure disorder is ever so much more effective. And then there is the complementary issue of dietary supplementation. Also there are newer medications, as well as more refined surgery procedures. It is useless to speculate. Our professional life has given us the opportunity to encounter many children who remind us of our son, who are similarly a mystery to their parents and to their medical practitioners, and to help them. Sue could never be shaken by anything that parents told her, because she had already been there herself.

Brian left us a journal that he kept in college. This gave us insight into how Brian’s understanding of himself and of his condition changed over the years. This is written up, with my commentary, in the book “Brian’s Legacy.”

Postscript

Perhaps the most remarkable feature of Brian’s neurofeedback experience was that nearly all of the concerns we had about him were alleviated with a single training approach, a single sensor placement and a single training frequency, what is called a “protocol.” Yet neurofeedback was a very comprehensive remedy for him. This makes sense if all of his difficulties could be traced in some fashion to the seizure disorder. One might argue, for example, that many of his problems resulted from sub-clinical seizure activity that disturbed brain function broadly. The rage behavior could be explained in this way, as well as the night terrors, the sleepwalking, and the episodic paranoias. With yet other symptoms, such as the depression and Asperger’s, this hypothesis is not helpful. With regard to depression, the neurofeedback must have altered the ambient set-point of nervous system functioning. And with regard to Asperger’s, the neurofeedback training must have activated neural circuitry for emotional regulation that previously had not been much engaged.

If all of these different aspects of nervous system functioning could be affected by one particular training protocol, then that implies rather broad and non-specific effects of the training. Our subsequent experience with neurofeedback has only confirmed that to be the case. An integrative model is called for, both with respect to causal factors in mental disorders and the mechanism of remediation. Much of brain-based dysfunction must be traceable to disturbances in the neuronal conversation (the ‘neural dynamics’), and a subtle challenge to that system can manifestly provoke a rather global re-organization toward more functional states.

The effectiveness of our approach means that disturbances in the neuronal conversation offer us the best model for understanding behavioral disruptions and other mental dysfunctions, even if they are the secondary consequences of chemical or other organic disturbances. And the breadth of our impact must mean that we are affecting the quality of the neuronal conversation rather generally. At this point, we are still near the beginning of the exploration of what is possible through the marshaling of the remarkable functional plasticity of our brains. And we are just at the beginning of the conceptual change that needs to occur to place our cerebral symphony at the heart of the discussion. Although we know better at the intellectual level, in actual practice our society is still mired in a dualistic perspective on our essential nature, and that dualism is sustained in the way the health professions are organized.

Neurofeedback lies at the nexus of the mind-body problem, the functioning of our neuronal networks, but up to this point the mind-body problem has remained a kind of demilitarized zone for the psychological and medical disciplines. And even as neurofeedback is becoming established, it is being recruited by both sides of this duality. On the one hand, neurofeedback is seen as an extension and empowerment of the psychological disciplines and the meditative traditions, and on the other it is seen as part of the more reductionist medical enterprise and of rehabilitation. Neurofeedback is seen as complementary to the core competences of each domain. It is becoming apparent that neurofeedback should be featured in the main tent rather than as a sideshow in both domains.