A Case of Chemical Injury and PTSD

by Carolyn McLuskie, MA, RCC and Siegfried Othmer, Ph.D.

by admin | October 1st, 2025

When someone comes for neurofeedback with severe symptoms, we are not likely to be confronted with a single, narrowly definable issue. In cases of chemical injury that significantly compromise health and functionality going forward, the issue is inherently complex because it quite naturally evokes a trauma response as well. The dearth of available remedies makes for dim prospects. And if that occurs in a person with a history of early emotional trauma, this additional ongoing trauma is a compounding factor on what is already a problematic presentation.

In such difficult cases we don’t expect quick recoveries. Fortunately, the potential client doesn’t expect quick or even substantial recoveries either. On the contrary, the client may well come with a deep sense of hopelessness, or at least an attitude of wariness, skepticism, with low expectations for recovery after years of living in a state of profound dysfunction. In the case history at hand, we are dealing with severe symptoms of dysregulation that had been resistant to conventional medical and psychological interventions for the 10 years that the client, a veteran, had been seeking help. And in this case, the veteran appeared to have given up hope of recovery and resigned himself to being on disability indefinitely, with attendant victim mentality.

Fortuitously, he noticed a business card for Phoenix Neurofeedback in his therapist’s waiting room and was sufficiently intrigued to make further inquiries. The veteran thus became highly motivated to undertake the training, and then, with the support of his psychologist, doggedly pursued his case manager to obtain approval for 60 sessions of neurofeedback at Phoenix Neurofeedback. After six months, the effort met with success.

We have had the opportunity to effect significant recovery in this veteran, who had a horrific early upbringing, a difficult personal life subsequently, and later suffered a severe chemical injury while aboard ship. This naval engineer had an anticipation-of-death experience when his ship, the HMCS Protecteur—a Canadian Navy supply ship, caught fire while at sea in the South Pacific, disabling the vessel. The fire required an 11-hour effort by the crew to bring it under control. For the next five days, the crew worked to keep the fire contained as the ship was towed to Pearl Harbor, HI, USA.

For the first two days, the veteran worked long hours on containment procedures in the smoking engine room with no respiratory protection, in a toxic and oxygen-deprived environment. Canadian naval personnel are required to use Self-Contained Breathing Apparatus (SCBA) for respiratory protection during a shipboard fire at sea. The required SCBA was finally provided on day three.

Working without protective respiratory protection for two days subjected the veteran to the toxic atmosphere. The resultant neurological damage caused severe and enduring nervous system dysregulation that disrupted the veteran’s ability to conduct normal activities of daily living for the next 10 years. It was not until the veteran had the benefit of neurofeedback training that he experienced improvement, as shown by the clinically and statistically significant improvements cited in this report.

The primary concerns at intake included the following: PTSD, anxiety, agitation, depression, emotional reactivity, mood swings, and a susceptibility to panic attacks. Additionally, the client was experiencing chronic nerve pain due to a torn Achilles tendon.

The treatment plan called for 60 ½-hour neurofeedback sessions conducted three times a week (Mon-Wed-Fri), following upon an initial 3-hour assessment, and a two-hour re-assessment at completion of treatment. The veteran was compliant with the program and attended sessions consistently.

Training began with three common starting protocols: {T4-P4} for calming of arousal; {T3-T4} for cerebral stability; and {T4-Fp2} for emotional regulation. After twenty sessions, not much had changed. By session 36 new protocols were in the mix: {T3-F7} and {F3-F4} for attention and mood regulation issues. Improved emotional regulation was reported, and by session 42 improved sleep was reported as well.

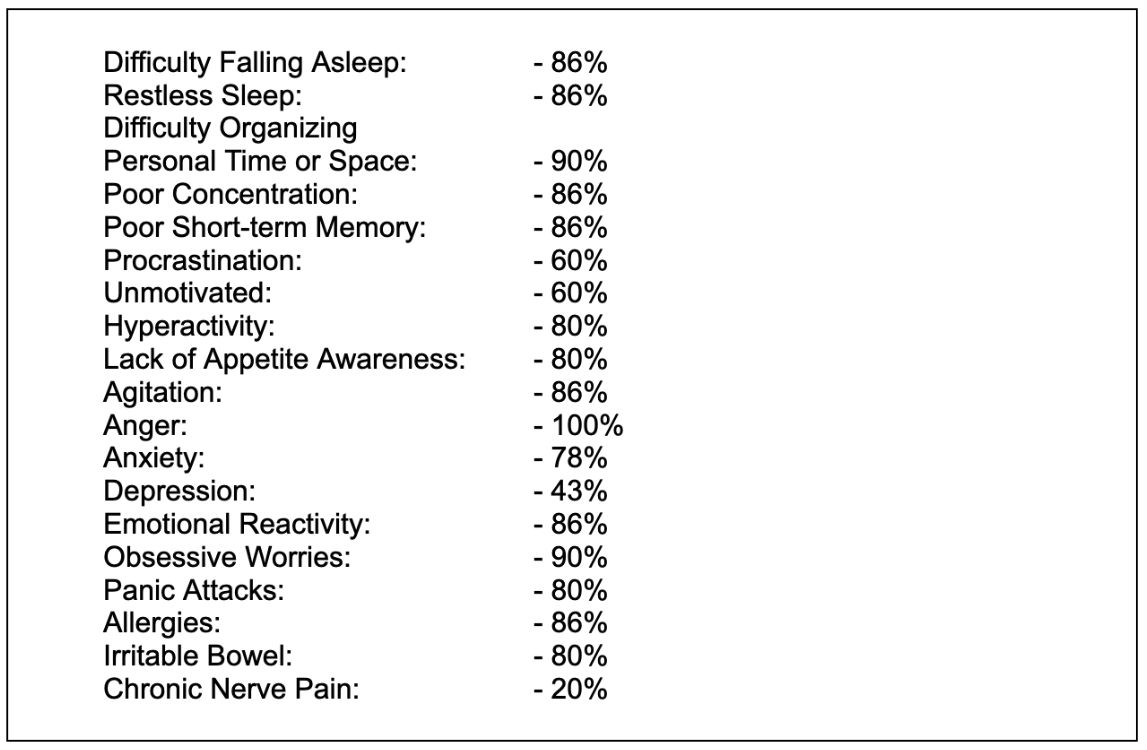

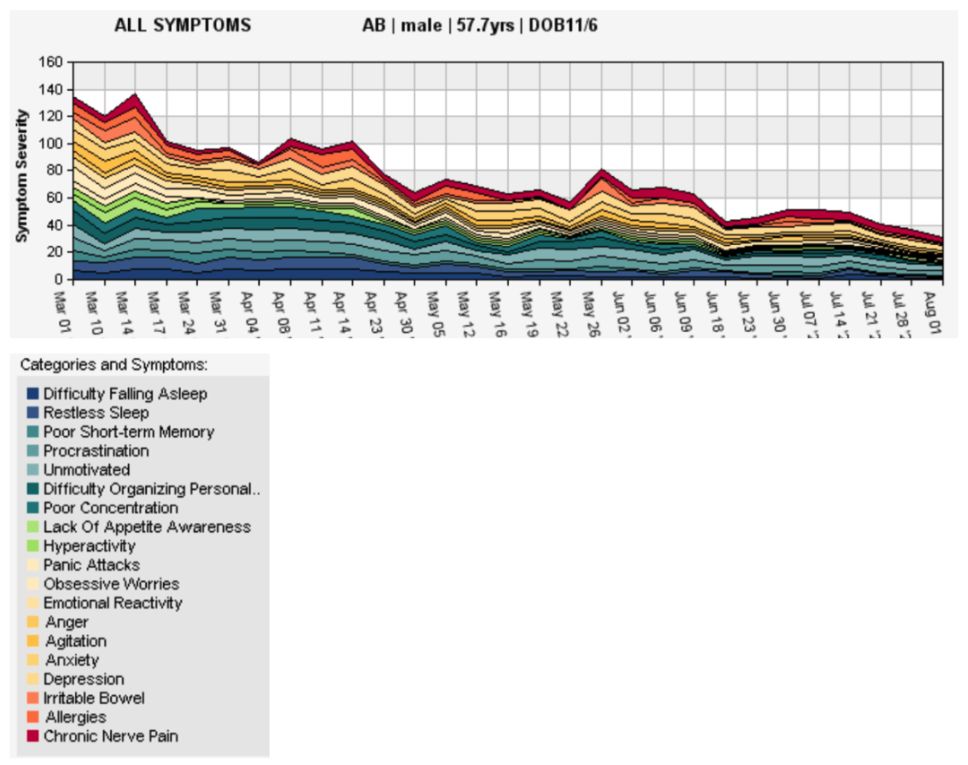

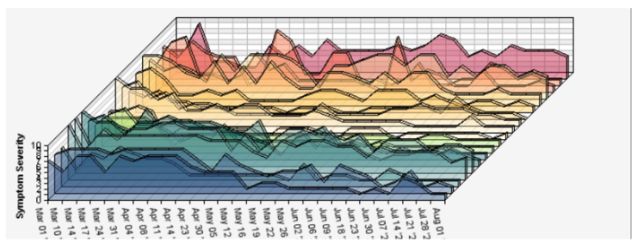

Symptom tracking, conducted weekly, showed an overall reduction in symptom severity of 77%. Symptom severity was ranked on a ten-point scale, with 1 or zero indicating symptom resolution. The only symptom that had not diminished significantly was nerve pain from the client’s damaged Achilles tendons. The only other significant residual symptom was depression. The improvements for specific complaints are shown in the box. This is represented graphically in Figure 1 and 2.

Figure 1.

Figure 2.

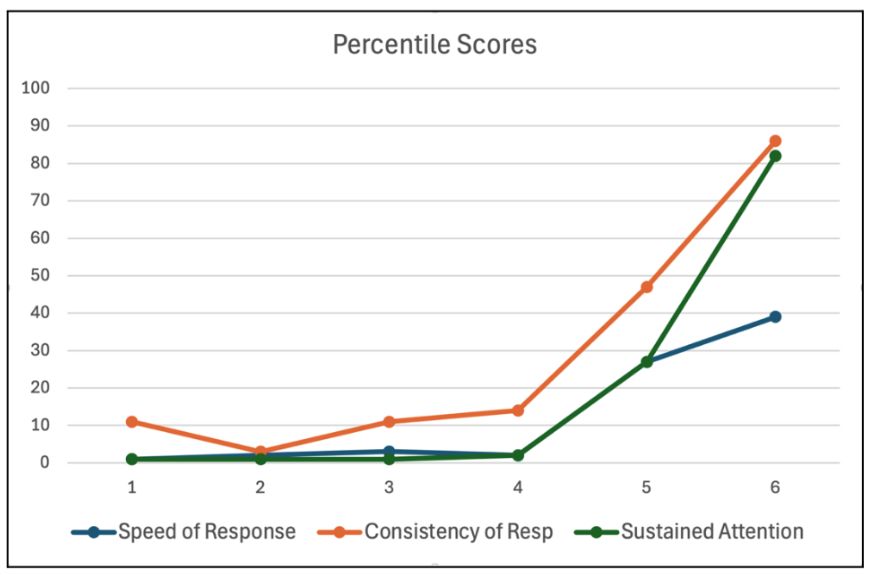

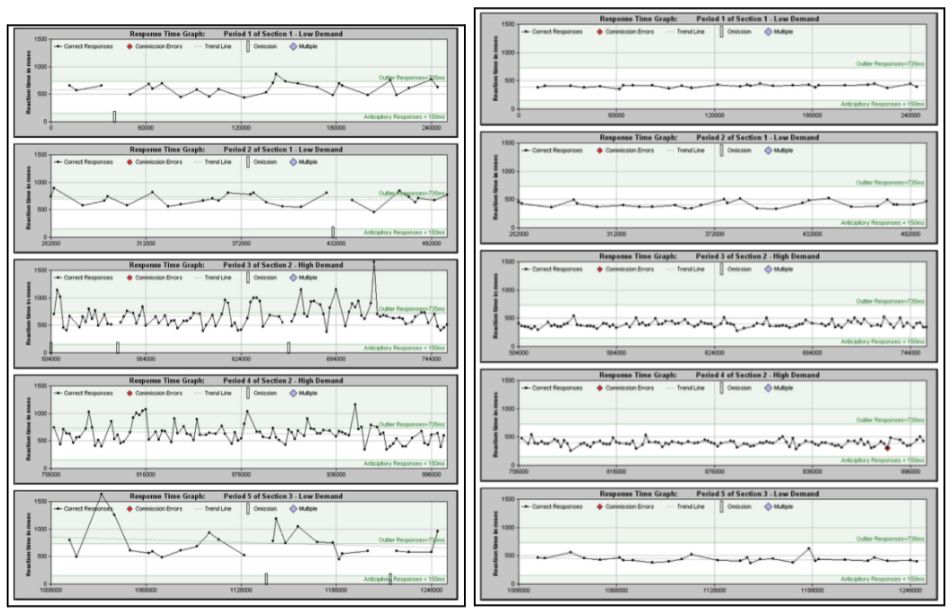

The QIKtest, a Go-NoGo Continuous Performance Test (CPT), was conducted to appraise attentional function and cerebral stability. The four principal measures tracked are sustained attention, as indexed by errors of omission; impulsivity, as indexed by errors of commission; mean reaction time; and variability in reaction time. It is most meaningful to express the results in terms of percentile scores with respect to the normative database.

Here the initial results were dire: The veteran was functioning at the first percentile level in terms of sustained attentional function and reaction time. He was functioning at the 11th percentile level in terms of variability. In consequence of the slow reaction time, there was no issue with impulsivity, the only measure found to be in the normal range. Progress in the measures was minimal over the first forty sessions, but radical improvement was observed over the last twenty sessions. At completion of the planned 60-session training, sustained attentional function had improved from the first percentile to the 82nd; mean reaction time had improved from the first percentile to the 39th; and consistency of response had improved from the 11th percentile to the 86th. These results are shown graphically in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

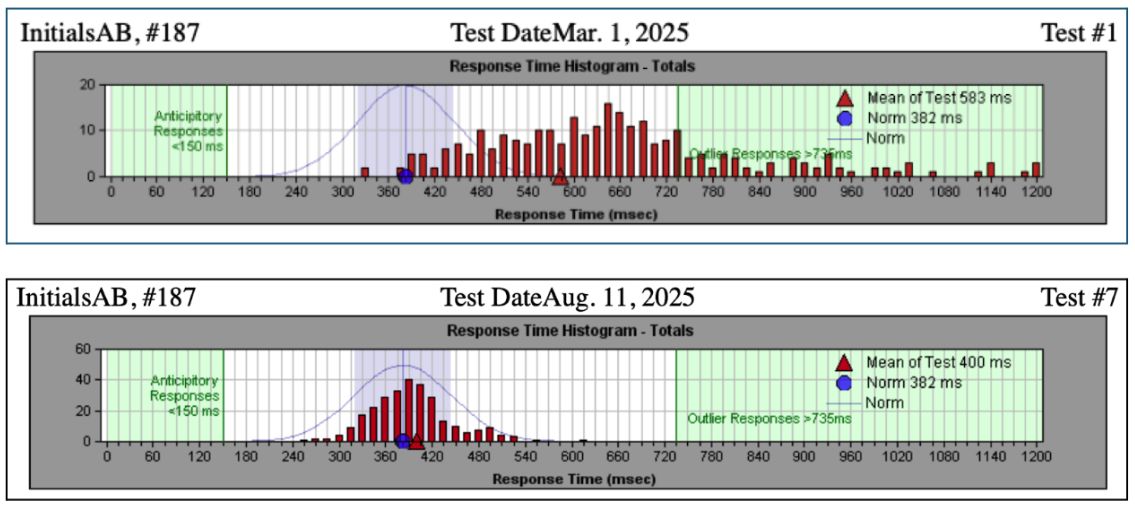

The pre-post changes in the distribution of reaction times are illustrated in Figure 4. And the pre-post changes in variability are illustrated in Figure 5.

Figure 4:

Figure 5.

Observations:

Significant changes were noted in the client’s attitude and emotional state as training progressed. He is now able to manage his emotions and maintain equilibrium even in situations where matters aren’t going in the direction he had hoped. Over time, he became more in touch with his desire to reengage in meaningful work. Initially, he had unrealistic expectations that vocational rehabilitation would involve upgrading his engineering skills so that he could reenter his trade at the level he left it. He has now accepted that the first step is to return to the workforce.

The veteran’s self-report at the conclusion of the training was positive: “I have had a lot of symptom reduction. My depressive symptoms came down significantly, as well as the symptoms that went along with that: disorganization, disruptive sleep, having a disruptive life. I feel more relaxed, not as agitated or upset, and I have an overall sense of wellness. I am way more focused. I am now able to respond more quickly to the events in my life, and I am more quickly able to get to my tasks.

“I am involved in a long-term legal case that previously triggered a fight-flight-freeze reaction and an internal dialogue that saw doom in everything. I am no longer reactive. Instead of always being worried, I have a more curious, wait-and-see attitude about events in my life. I can think on my feet, rather than getting stuck in negative thinking patterns.”