Brain Hacking

by Siegfried Othmer | June 5th, 2015by Siegfried Othmer, PhD

The June issue of The Atlantic Magazine features an article on brain hacking by Maria Konnikova. The article reviews various technology options that give some hope of sprucing up brain function. First of all there are the smart pills. Already the stimulants are finding use beyond their medical applications in boosting test performance among college students.

The June issue of The Atlantic Magazine features an article on brain hacking by Maria Konnikova. The article reviews various technology options that give some hope of sprucing up brain function. First of all there are the smart pills. Already the stimulants are finding use beyond their medical applications in boosting test performance among college students.

Transient DC stimulation is discussed as an option for a brief performance boost that might endure for an hour or two. Even deep brain stimulation such as is used for Parkinson’s gets a surprising mention.

Over the longer term, options of brain re-engineering may emerge through the exploitation of genome editing. That’s heady speculation indeed. Why not? We’re in the era of wild optimism with regard to the exploitation of brain plasticity.

Overlooked in this orgy of prognostication is that we have a perfectly good technique already in our hands that exploits brain plasticity marvelously and achieves all of the desired ends and more. In order to be able to see it for what it is, however, one needs to shift perspective.

All of the methods mentioned in the article have at least one thing in common: they all involve human agency along with external manipulation of brain function. They put man in charge of the project of enhancing brain function, which implies a state of knowledge on our part that does not yet exist. Our present primitive methods of intervening with the brain are an insult to the brain’s complexity and its inherent competence!

Is there an alternative? Indeed there is. We can place the brain in charge of improving its own function, which means exploiting the full complexity of the brain in pursuit of that objective. This means that instead of coaxing the brain to perform at higher levels of function we first seek to eliminate impediments to good function. Better performance follows. If performance limitations can be traced to identifiable deficits in brain organization, then certainly these ought to be our first concern.

The brain we possess is what we have left after the brain has run the gauntlet of minor insults while it was developing and maturing. Perhaps the first such insult was squeezing through a too-confining birth canal. Beyond that, nearly all have suffered a variety of minor physical insults, emotional traumas, and physical illnesses on the pathway to maturation. Chances are that since you are reading this, you are doing fairly well despite any such handicaps. We may not even be aware that there were any handicaps at all. If we are mentally healthy, most likely we largely accept ourselves as we are.

This benign state of affairs is attributable to the plasticity of our marvelous brains, and to their recovery capability. Our brains have almost magical cover-up skills with respect to their own flaws—provided they are modest. So how do we prove our hypothesis that most of us are laboring under remediable constraints? We do it with the acid test of empirical proof. If we can get the brain to improve its IQ score systematically solely by means of a boot-strapping technique, then we would regard the hypothesis as proved. This we have done beyond our wildest expectations.

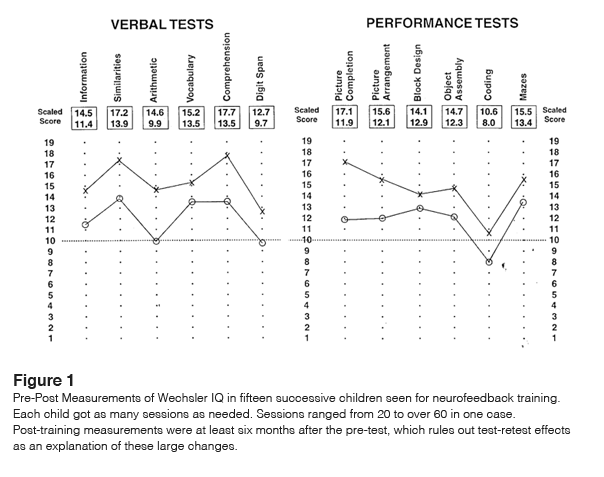

The first Figure shows the improvement in Wechsler IQ score achieved with fifteen successive ADHD children who trained their brains at our office. No other brain assist was involved, medical or otherwise. An average improvement of 23 points was observed in IQ score, even though the average value at the start was already above norms at 107. The group ended up at an average score of 130, two standard deviations above the population mean. The results were plainly astounding, and far exceeded our own expectations. The changes are large enough that they cannot be explained away on the basis of test-retest error. In fact even larger changes have been observed, on the order of forty points in IQ score, in individual cases. That can change lives.

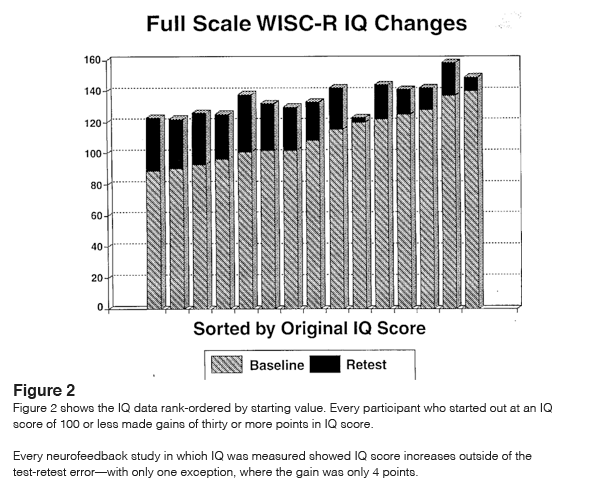

If we rank-order the cases in terms of starting value of IQ score, we find that all of those who started out at a score of 100 or below gained on the order of 30+ points. This is shown in the second Figure.

So before we start drugging or zapping the brain, implanting electrodes or venturing genetic modification for functional enhancement, perhaps we simply ought to give the brain the means to get out of its own way. As this is a strategy of remediating impediments to function, it is expected to work best for those whose dysfunctions are manifest. But our hypothesis is that every brain experiences brain insults in the course of growing up, and that the first priority with every brain ought to be redressing the resulting impediments to function.

We may not see major improvements in IQ in someone who is already far above average, but the effort will most likely be worthwhile nonetheless. Everyone has both strengths and weaknesses in brain function. Most of those who already function extremely well seek us out in order to enhance their skills even further. Others may want to shore up their weaknesses. We have no idea how well our brains are capable of functioning until they are given an opportunity to resolve their own shortcomings.

The pathway to better function is rather straight-forward, it turns out, just as long as we don’t try to impose our own limited perspectives on our marvelous brains. For its own purposes of improved self-regulation, the brain needs information; it does not need instruction. We understand the process as a kind of skill learning, by analogy to learning a performance skill such as dancing.

The brain enhances its skill in the dance by observing the dance. This concept translates directly into the project of training brain function generally: We just have to show the brain its own dance, and it proceeds to refine its own skills in consequence. Matters could hardly be simpler at the conceptual level. Unsurprisingly, they are a bit more complex in the actual process.

Whereas we can observe the brain’s execution of an actual dance, we are not privy to the dance of internal regulation. It lacks external observables. However, through the aid of modern instrumentation we can make the brain visible to itself. Brain behavior is reflected in glorious complexity in the EEG. The EEG turns out to be the best analogue of the brain’s dance that we have. The signal is too complex for our ready interpretation, but it is exquisitely recognizable to the brain in real time. This, then, is the process: The brain witnesses its own unfolding EEG, and it benefits from the experience.

The hypothesis has been proved. Brain function can be substantially improved by sole reliance upon the existing resources of the brain. We do not need to await the invention of new gadgetry or new drugs, and we don’t need to wire up the brain or implant chips. We simply charge the brain with the burden of enhancing its own performance, and we do so by effectively holding a mirror up to it and allowing it to see itself in action. Significantly, even though we posited impediments to good brain function, the method is not actually targeting any such impediments. It is just aiming for better function. Dysfunctions subside as a secondary consequence of the enhanced functionality. In this elegant approach, function banishes dysfunction. No diagnoses needed.

References

Improvements in IQ Score and Maintenance of Gains Following EEG Biofeedback with Mildly Developmentally Delayed Twins

Matthew J. Fleischman and Siegfried Othmer

Journal of Neurotherapy, 9(4), 35-46 (2006)

EEG Biofeedback Training for Attention Deficit Disorder, Specific Learning Disabilities, and Associated Conduct Problems

Siegfried Othmer, Susan F. Othmer, and Clifford S. Marks

Journal of the Biofeedback Society of California, September 1992.

EEG Biofeedback: An Emerging Model for Its Global Efficacy

Siegfried Othmer, Susan F. Othmer, and David A. Kaiser

In Introduction to Quantitative EEG and Neurofeedback, James R. Evans and Andrew Abarbanel, editors, Academic Press, San Diego, pp. 243-310 (1999)

EEG Biofeedback: Training for AD/HD and Related Disruptive Behavior Disorders

Siegfried Othmer, Susan F. Othmer, and David A. Kaiser

In Understanding, Diagnosing, and Treating AD/HD in Children and Adolescents, An Integrative Approach, James A. Incorvaia, Bonnie S. Mark-Goldstein, and Donald Tessmer, editors, Aronson Press, Northvale, NJ, pp.235-296 (1999)