The Medical Treatment of Epilepsy

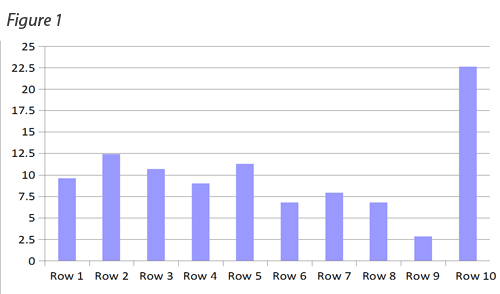

by Siegfried Othmer | August 28th, 2009 An informal survey taken on a public website dealing with epilepsy has found a notable trend in the prescribing of anti-convulsant medication. Most people being treated for epilepsy have been tried on a significant number of different medications. The survey results are shown in Figure 1. Shown is the percentage of respondents who have taken the indicated number of medications over their treatment history. The bin labeled ’10’ includes everyone who has been prescribed at least ten different anti-epileptic drugs. The modal value is ’10,’ so those diagnosed with epilepsy are more likely to have been prescribed ten or more medications than any lesser value. The total number of participants in the survey was 177.

An informal survey taken on a public website dealing with epilepsy has found a notable trend in the prescribing of anti-convulsant medication. Most people being treated for epilepsy have been tried on a significant number of different medications. The survey results are shown in Figure 1. Shown is the percentage of respondents who have taken the indicated number of medications over their treatment history. The bin labeled ’10’ includes everyone who has been prescribed at least ten different anti-epileptic drugs. The modal value is ’10,’ so those diagnosed with epilepsy are more likely to have been prescribed ten or more medications than any lesser value. The total number of participants in the survey was 177.

No doubt each of these medications required several visits to the neurologist, plus some blood work and perhaps an EEG every now and then. Also we may assume that most of the ten or more medications will have been abandoned along the way because it is unusual for someone to be on more than three AEDs at a time. So one may judge that at least 70% of the ten or more medications were not worth keeping in the mix. That indicates a fairly low hit rate on the medications.

Further, we may fairly judge that the affected individuals who contributed to the survey are not satisfied with their current medical status because they sought out an epilepsy support website. Of course that also makes this a biased sample. Happy customers are less likely to show up here to contribute to the survey. It is also likely that a group like this attracts seekers who are relatively young in their epilepsy career, who have not had time to accumulate a long medication history. The survey is a snapshot of a status that is on a path to getting worse over time. If the same people were to be surveyed at a later date, the curve could only look worse; it could not look better, as people can only move to the right on the curve or stay where they are.

It is the medically refractory cases of epilepsy that find their way to neurofeedback, so our client sample may very well be similar to the population reflected in Figure 1. (We don’t often see people whose seizures are controlled, even though they may be suffering significant side effects.) Our clinical experience is much better than what is implied in the figure with regard to meds. There is first of all a significant likelihood that trainees will become entirely seizure-free with neurofeedback. This percentage was only five percent in the research summary Sterman published in 2000 that covered the early research history of the field. There has been considerable advance in the technology and in the protocols since then.

Even back then, the average improvement was greater than 50% in seizure incidence. This would not be a bad outcome for the addition of a second, third, or fourth medication. But even that pales in comparison to outcomes with modern neurofeedback procedures. Further, both then and now there is the promise of a decrease in seizure severity. And finally, both then and now the resort to neurofeedback may permit a reduction in medication dose so that adverse side effects are reduced.

Just in terms of the raw data, then, neurofeedback compares favorably to polypharmacy for epilepsy in all relevant aspects. But there is more. The neurofeedback training is likely to take only a finite commitment of time, and beyond that no further care may be required. Even if an occasional booster session is found to be worthwhile, that can often be self-administered at home under remote clinical supervision. Neurofeedback promises substantial improvement in the quality of life for most persons with epilepsy. Further, the Othmer Method offers some particular advantages with respect to training the brain toward greater stability by virtue of our utilization of inter-hemispheric training and the inclusion of the infra-low region of EEG frequencies, which at the moment remains unique within the field.

If neurofeedback is so much better than anti-epileptic drugs used in combination, perhaps the assumptions underlying polypharmacy need some updating. AEDs influence the excitability of neuronal membranes. Neurofeedback influences the excitability of entire neuronal networks. Reducing matters to their simplest essence, AEDs target ligand-gated ion channels, whereas neurofeedback presumably targets voltage-gated ion channels. The two are entirely complementary. Once two or three different AEDs are at work, most of the benefit derivable from AEDs has probably been plumbed. Far better to add a complementary technique that works by a different mechanism toward the same objective.

In addition to any modulation of local neuronal excitability that neurofeedback may effect at the site where seizures are kindled, there is also a diffuse network effect that impinges on the likelihood that a local paroxysm may generalize into a seizure. A subtle rebalancing occurs which alters the excitatory/inhibitory relationship in the neuromodulatory networks. This is the unique contribution of neurofeedback, and most likely represents the dominant mechanism in the diminution of seizure susceptibility. We are now in a position to enhance overall network stability in a predictable fashion with well-validated protocols.

In one perspective, seizures represent a relatively “trivial” problem for neurofeedback. Let me explain. In most cases that we encounter in clinical practice, seizures are relatively rare events. That is to say, the brain spends most of its time in a reasonably controlled state, with only occasional breakdowns into instability. We are working with brains that are “almost stable.” All that is necessary to do is to enhance the mechanisms that ensure stability which the brain already has access to. Progress just needs to be modestly incremental in this regard to increase the probability of seizure-free existence from, say 99.999% to 99.9999%, i.e. from five nines to six or even seven nines. That translates into a reduction in seizure incidence by a factor of ten or one hundred. If that is the case, then it shouldn’t take much more to render a person entirely seizure-free, and that is indeed what we observe. Some medically intractable epileptics become seizure-free quite quickly with this training. There is no way currently to predict such outcomes. The training simply has to be tried.

The avoidance of unnecessary medications is a worthy objective all by itself, but even this pales in comparison to the avoidance of unnecessary brain surgery. Throughout the history of the field, the experience has been that a substantial fraction of those scheduled for brain surgery for the control of seizures were able to avoid the surgery after doing neurofeedback. That being the case, it should be ethically mandated that neurofeedback be tried before brain surgery is undertaken.

This is how cost reduction in health care will be achieved. It will be done by enhancing outcomes using innovative new methods—even if they are already forty years old.

Resources:

Basic Concepts and Clinical Findings in the Treatment of Seizure Disorders with EEG Operant Conditioning, M. Barry Sterman, Clinical Electroencephalography, 31(1), p. 45-55 (2000)