Bill Gates abandons search for the “Big Idea” in Education

by Siegfried Othmer | September 28th, 2018So reads the feature article in the Los Angeles Times on Aug. 29. Unfortunately, he does not know about Infra-Low Frequency (ILF) Neurofeedback, because if he did, he would realize at once that this is what he has been looking for. As a software guy, he realizes that the brain is the singular entity in the universe that writes its own software—the software that supports its own function. This is a long-term bootstrapping operation. And since brain function is not gifted equally to everyone, it follows that some brains are better at writing their own software over the course of development than others. Are we compelled to live with that situation, as we have been doing forever, or can that process be aided?

Those of us working with neurofeedback know that the process can be substantially aided. Brain development can be modeled as a software project, something that ought to be amenable to alteration. How might that play out in the real world? We know that the brain acquires its skills through practice. Neurofeedback supports that process instrumentally, and people benefit in a variety of ways. But what concrete evidence can we furnish that makes the case beyond the reach of skepticism? Consider just two characteristics that concern us specifically during the school years: inattention and impulsivity. These can be taken as indices of progress in brain maturity, in that we all start out in life as distractible and impulsive.

The reason for choosing these particular characteristics is that they are commonly assessed with a continuous performance test (CPT), a computerized tool with computerized scoring. So we have an objective measure that is independent of human judgment. The CPT is well-accepted within neuropsychology, and we have norms for all ages above five. As it happens, we have just done a survey of CPT results for our entire practitioner network of several thousand clinicians around the world. The results are therefore fully representative of what happens in actual clinical practice. The survey could be efficiently done because all of the data are stored on a central server. They cover a period of over ten years, from 2007 to 2017. The measurements were performed on a QIKtest, a CPT test that emulates the TOVA in its design, but has the benefit of up-to-date norms for our modern, fast-paced existence and nimble-fingered youth. The total sample consists of nominally 12,200 cases that have undergone twenty sessions of training with ILF neurofeedback by the Othmer Method. The survey is therefore directly relevant to this particular approach to brain training.

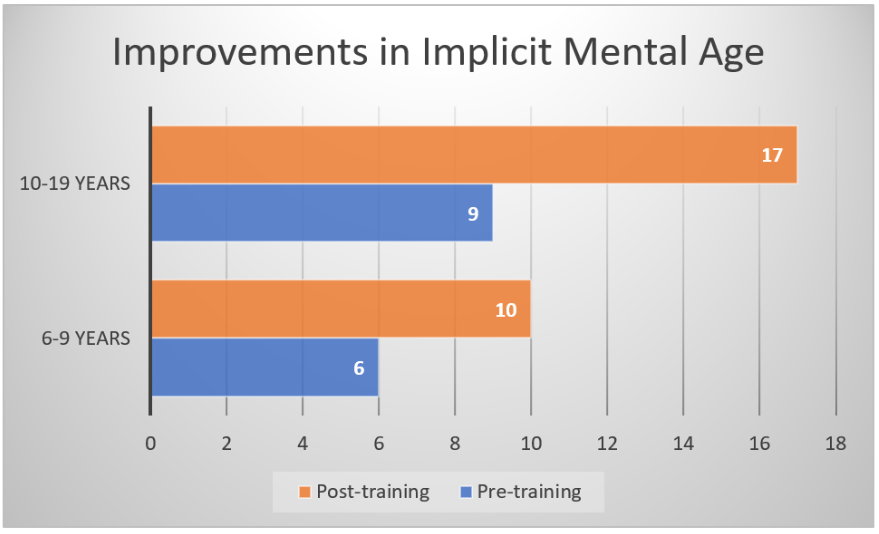

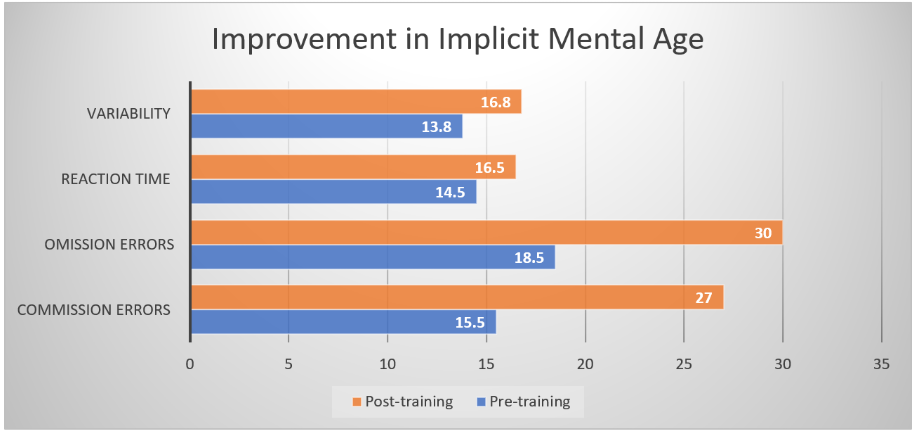

The 12,200 cases cover the entire age range of 6 to 70 and above; they include the complete range of complaints that bring people to neurofeedback. Many young people do come to us because of attentional and behavioral issues, but adults typically come with other complaints. As may be seen in Figure 1, which shows the group data applicable to impulsivity, all children between six years and their tenth birthday test out with a median value of just under six years of age. After twenty sessions, the median value for this group of children is just over ten years. One can say, in broad brush, that the bulk of the sample, some 2680 children, has moved up four years in mental maturity with respect to the issue of impulsivity. That is huge.

If we do the same with the children and adolescents older than ten but short of their twentieth birthday, we find that this group tests out at a median value of 9 years before the training. After twenty sessions of training, the group tests out at a median value of 17 years. The bulk of the group has moved up some eight years in mental maturity with respect to impulsivity. These data will strike many professionals as too good to be true. That’s been the story of neurofeedback. When clinicians report stunning results, they are met with incredulity. But these statistics are inescapable in their implications. They leave no wiggle room for skeptics. The 10-19 age cohort contains 5430 individuals.

Figure 1. Improvements in equivalent mental age for errors of commission, which index impulsivity, for the 6-9 and 10-19 age cohorts.

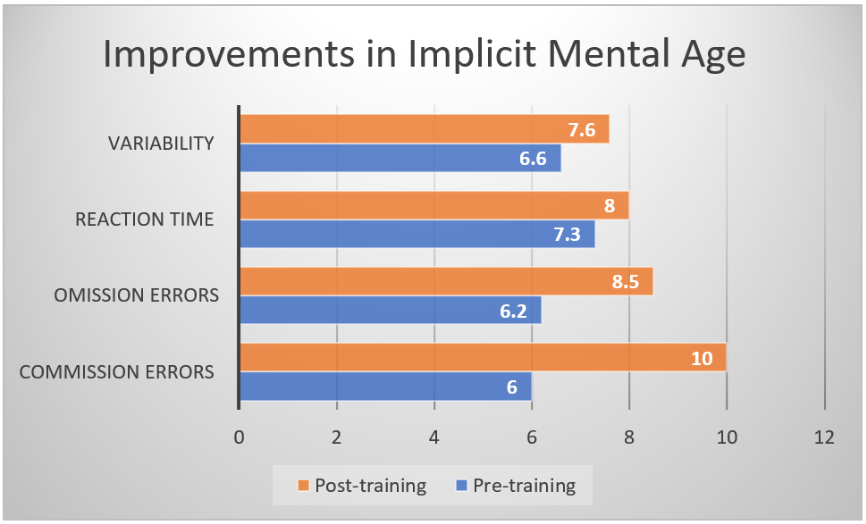

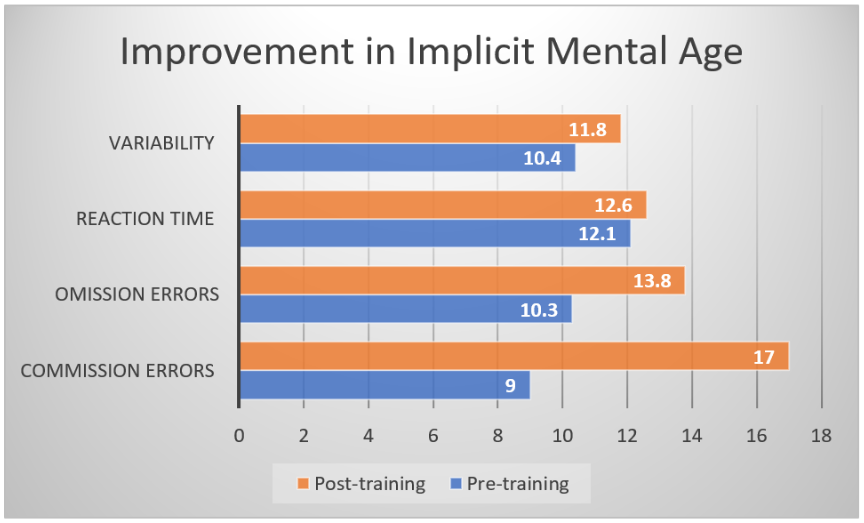

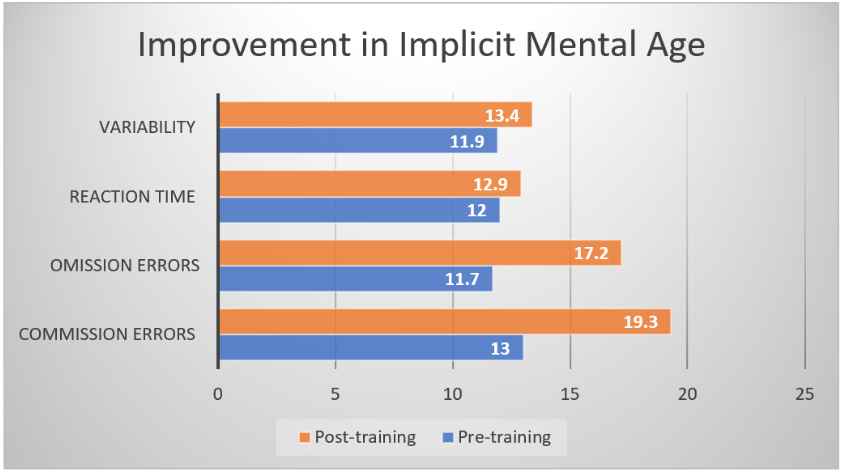

The CPT also gives us information on inattention, on the average response time, and the consistency achieved in the responses. For the 6-9 year cohort, the results are shown in Figure 2. The improvement in median mental age is 2.3 years for inattention, and we even see improvements in reaction time (8 months) and in consistency (one year). Data comparable to that in Figure 2 are shown in Figure 3 for the age cohort 10-19. The results for the entire age range are shown in Figure 4, representing the total population of 12,200.

Figure 2. Improvement in the four primary measures of the Continuous Performance Test, expressed in terms of equivalent mental age, for the 6-9 year cohort. (N = 2680)

Figure 3: Improvement in the four primary measures of the Continuous Performance Test, expressed in terms of equivalent mental age, for the 10-19 year cohort. (N = 5430)

Figure 4: Improvement in the four primary measures of the Continuous Performance Test, expressed in terms of equivalent mental age, for the total sample, covering all ages from 6 to 70 and above. (N = 12,200)

Finally, for comparison purposes the accumulated data are shown for the EEG Institute in Los Angeles, lead organization for ILF Neurofeedback, in Figure 5. The client population here tilts toward a greater age, on average, than what holds for the practitioner network as a whole. A complete normalization of scores is indicated (for the medians of the population), in that performance reaches its optimal value in the age range of 25-35.

Figure 5. Improvement in the four primary measures of the Continuous Performance Test, expressed in terms of equivalent mental age, for the total sample, covering all ages from 6 to 70 and above, for the EEG Institute in Los Angeles.

If Elementary and High School teachers around the country were asked, they would certainly see the above as a big thing. But there is more here than meets the eye. Compare neurofeedback with stimulant medication for ADHD, for example. With stimulant medication, the target is improved impulsivity and inattention, but this is achieved with what might be called ‘narrow targeting.’ The stimulants help mainly with impulsivity and inattention, but not with much else. With respect to other issues such as sleep quality and appetite regulation, reliance on stimulants may leave people even worse off. The children and adolescents that come to us labeled with the diagnosis of ADHD typically have more issues than just the cardinal symptoms of impulsivity, inattention, distractibility, and hyperactivity. We see them as living with a more global problem of dysregulation.

In the case of neurofeedback, we are training the whole brain, with benefits observed across the board. We expect to see improvements in sleep quality, in emotional regulation, and in improved academic skills. Rages, if any, should subside. Bed-wetting, if it is still an issue, should end. Oppositionality should fade. Mood swings should moderate. And pain syndromes, including head and stomach pain that are commonplace in children with ADHD, should subside. Academic performance should improve. The biggest and most consistent benefit is a heightening of self-esteem, and that is for the best of reasons. Trainees will have a lot more to be proud of, for one thing, but even more important, they will have established a more solid sense of self. So for us in neurofeedback, impulsivity and inattention serve as convenient indices of general progress. They are not the primary focus of our client’s attentions or ours in the general case.

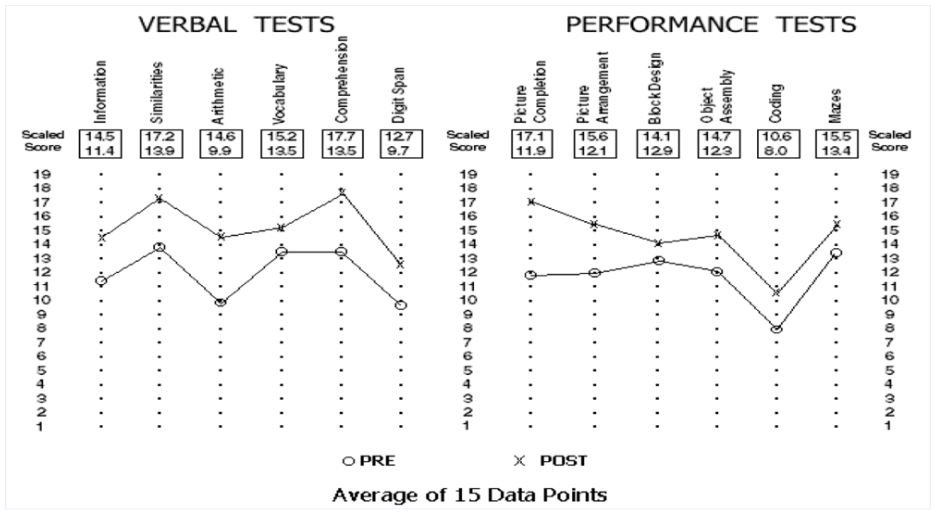

With neurofeedback we also see systematic improvements in IQ test results. This can also happen with stimulants, but that is seen only rarely. Improvement in IQ test scores and in academic skills is not an expectation with stimulants. With neurofeedback, we do expect to improve the person’s IQ scores, particularly if these are deficient. Here, for example, are the test results for the WISC-R IQ for fifteen children on the ADHD spectrum, both before and after neurofeedback training. The average improvement in IQ score was found to be 23 points. The average IQ improved from 107 to 130 (100 is average).

Observe that the IQ’s were already in the normal range prior to the training. The neurofeedback training facilitates the brain’s rise to its full potential, whatever that may be. A big issue in this sample of ADHD children is that the behavioral issues were so severe that they did not really care about how they did academically. Once their behavioral issues were resolved, they were more eager to do well on the test. In a larger sense, then, these children ‘found themselves’ in neurofeedback. Teachers will surely relate to the issue of ‘not caring’ among their pupils. The problem has a remedy, and it is neurofeedback.

The implication of all of the above is that we really have no idea about the inherent competence of our brains until they have a chance to hone their skills with the help of neurofeedback. Neurofeedback simply aids the brain in the writing of its software. As already said at the outset, this is a matter of skill learning. The brain learns by observation of its interaction with the outside world. We are giving it information on its own activity. Call it ‘Augmented Reality’ for the brain. The brain takes advantage immediately—and it is capable of doing so at any age. That is indeed a very big thing.