By Law or Grace

by admin | February 24th, 2005Glen Martin has been involved in neurofeedback since 1993. He happened to be home sick on January 12 th of that year, and tuned in to the Home Show at which we demonstrated our neurofeedback instrument. The economy was in the doldrums at the time, and his own office finances were iffy, but nevertheless he took a gamble on neurofeedback and became one of the early members of the EEG Spectrum affiliate network. The principal driver was the identified ADHD of his son, whose training eventually turned into quite a saga. His daughter benefited as well, and ultimately his father also.

Both Glen’s professional and family involvement with neurofeedback have been quite remarkable adventures, and I will return to these below. But in a further turn of events, Glen became more and more concerned about the “parenting deficits” that he was seeing among the desperate families coming to him with their oppositional and bipolar children. Eventually Glen decided to make that his focus rather than the neurofeedback. The result is a new book that he has just self-published, titled “By Law or Grace.”

Glen and his co-author Maggie DeMellier reflect on the major trend in parenting over the years in the US, going from the more regimented, prescriptive style of parenting to the more accepting, permissive style. The former he called the “Respect Model” and the second the “Self-esteem Model.” The former is discipline-based and rule-based, emphasizing external control, whereas the second is based on an appeal to internal control on the part of the child, based on feelings and habits of thought.

The shift in parenting styles has been global in the Western world, and from the mental health perspective is to be welcomed as more humane. However, it has failed to take into account that there are broadly speaking two types of children, externalizers and internalizers, and in some sense we have simply moved from disadvantaging one of these groups to disadvantaging the other. Externalizers tend to be concerned with their own needs, and less sensitive to the needs of others. Internalizers, on the other hand, are overly sensitive to the needs of others and insensitive to their own needs.

The traditional rule-based parenting style in fact suited the externalizer quite well, and succeeded in socializing them. At the same time, the price paid was often the traumatization of the internalizer for whom this parenting style was totally inappropriate and counter-productive. Now that we have as a society moved toward the more gentle self-esteem model, we find the internalizers thriving and the externalizers collectively and individually going out of control. They simply require the external controls that were traditionally imposed on all children.

The one-third of children who are to be found at one end of the spectrum or the other will be ill-served by any such homogeneous prescription. Parents may need to have both styles in their inventory for their children, as indeed they may have both internalizers and externalizers among their offspring. Parents also need to be aware of their own place in this scheme of things, insofar as their own suffering at the hands of their parents may now be reflected in adjustments of parental style that may be inappropriate to some of their children. The worst situation for the parent is when they themselves are internalizers and their children are externalizers. The worst situation for the children is when the parents are externalizers and the children are internalizers.

Other dichotomies are discussed in the book, such as whether the children function out of a more rational perspective, the “head-place,” or out of the emotional perspective, the “heart-place.” The combination then makes for a basic categorization into four major types: Externalizer/Head person; Externalizer/Heart person; Internalizer/Head person; Internalizer/Heart person. It may strike the reader, particularly the mental health practitioner, that the distinctions being made here are so obvious, once they are pointed out, that they shouldn’t require a book to elucidate them. We know about the introversion/extraversion dichotomy of Hans Eysenck, and about the traditional left hemisphere/right-hemisphere dichotomy.

On the other hand, most parents don’t have these models in their heads. Perhaps apparent obviousness just means that the time is ripe for such a parenting model in our society. At the consumer level, the message must be relatively straight-forward. We have certainly paid a huge societal price for our inappropriate parenting styles. At this point, our approach to the externalizer is to drug him or her into submission. The externalizers’ own response may be to resort to the street pharmacy. The inadequately socialized externalizer may be looking at a career of criminality, addiction, spousal abuse, con artistry, and “just about anything that involves power and control gone wrong.” The overly constrained internalizers, on the other hand, may live with an excess of fear and can become chronic victims, abused spouses, underachievers, and codependents, perpetually suffering from low self-esteem.

At some point, of course, the dichotomies break down. When it comes to Reactive Attachment Disorder, for example, the basic issue may go back to the fear response, but it may be expressed in an extraordinary need to control events and persons. Glen is aware of the shortcomings of any such simple classification, pointing out that both Adolf Hitler and Mother Teresa would be characterized similarly as extreme externalizers coming out of a heart place.

The bulk of this very small, easily digested book deals with aspects of the two parenting models, the Respect Model and the Self-Esteem model, the Law Style and the Style by Grace. Neurofeedback practitioners may want to have this little book in their waiting rooms, and perhaps available for sale as well to the parents who may need it.

At this time only a small number of books has been printed. This gives an opportunity for some serious editing that the book still needs. We have a few books left at the office from Winter Brain Conference, for anyone interested ($15.00)

Glen Martin’s Adventures with Neurofeedback

Some years ago Glen told me the story of a child he began to train with neurofeedback for ADHD. The training had just gotten underway when the mother abruptly pulled the child from training. Her pediatrician had told her that the child does not need neurofeedback. He just needs a little Ritalin. He pacified her concerns by saying that Ritalin was no more of a risk than eating M&M’s would be. The mom trusted the pediatrician’s advice.

A year or so later their paths crossed, and Glen inquired of the mom how her child was doing. It was a long story. The child had not thrived with the Ritalin. Not to worry, said the pediatrician. We’ll just add an anti-depressant. Some months later, that did not turn our well, either. So by the time the conversation took place a year hence the child was on four major medications, including one of the new anti-psychotics and a mood stabilizer along with the stimulant and the anti-depressant. The last time Glen spoke with the mother was at a C.H.A.D.D. meeting. The pediatrician had told her that these medications were all perfectly safe and that EEG Biofeedback was unnecessary, even though she admitted her son was not doing well at all. The child was at this point not quite eight years old. Glen saw this as a kind of A/B comparison with his own son, who by this time was recognized as exhibiting childhood Bipolar Disorder, and was thriving with neurofeedback.

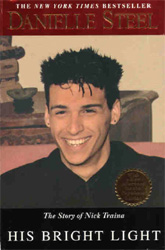

Along the same lines, an even more remarkable comparison to his own child was to be found in the book “My Bright Light,” by Danielle Steel. It was almost as if Steel’s son was a “Doppelgaenger” for his own son. The similarities were numerous. And it was another A/B comparison of conventional treatment of childhood Bipolar Disorder with neurofeedback. Given the commonalities between the two situations, Glen was moved to write to Danielle Steel. Of course it is difficult to pierce the protective barrier around celebrities. It is doubtful that the letter ever reached its addressee. The letter does, however, cover Glen’s early history with neurofeedback, and bears repeating at least in part.

11/10/00

Dear Danielle Steel,

My wife has read all of your books. Last year for the first time she asked me to read one of them. The reason she asked me to read this particular book is because of the remarkable similarities between your son and ours.

Our son is also named Nick. Nick is currently 21 years old. The love of his life is Sarah, his childhood sweetheart. He was a big baby and my wife, Beth, also had to have a C-section. Nick was a beautiful, happy infant. He, too, started talking in complete sentences before he was one year old. A precocious child, I found him one day picking out tones on a toy piano when he was 4 years old. We were told he had perfect pitch.

Nick, however, became more difficult as he grew older. When we went to the teacher’s conference, his fifth-grade teacher broke down in tears. Being a young teacher, she sobbed that maybe she had gone into the wrong profession. It was difficult to get baby-sitters for him and even his grandparents would make excuses why they couldn’t watch him. One day I took him to a children’s karate school and the karate instructor said I should take him home and beat him.

The karate instructor, who worked only with children, said Nick couldn’t come back. Nick went on a bus trip with the Scouts and the parent chaperones wanted to send him back on a plane. They were serious. They actually started a fund for his airfare. Nevertheless when he wanted he could be incredibly charming, loveable and sweet. Some teachers could see past his problems and loved him dearly. His younger sister Anita adores him. Nick has a heart of gold.

Nick continued, however, to get more difficult as he got older. To use your phrasing, in seventh grade he not only started slowly downwards, but it was the beginning of disaster. Grades started to decline. Impulsivity increased. Already having broken a couple of bones, he broke three more bones in a nine-month period. As he went into high school his impulsivity continued to increase. He started dyeing his hair different colors, including green. Waking up and going to sleep became more and more of a power struggle. He wanted to stay up all night and sleep during the day. He could get by with very little sleep. We started getting telephone calls and letters from the school more and more frequently. In tenth grade he crashed. His grades dropped to a 0.7 GPA. He went from detentions to suspensions and finally to expulsion. The school had wanted him medicated for ADHD, but because he had tics we refused. My wife, a physical therapist, said she had seen too many children develop severe tic disorders who only had mild tics before the medication.

Finally he was expelled from school on a Wednesday. I was going to an out-of-town EEG Biofeedback workshop on Thursday. My wife asked me what I was going to do with him. I said I was going to take him with me to the workshop. At times, such as traveling, he could be a delight to be with. When we got there the instructor wanted a volunteer, so I quickly volunteered my son. The instructor, who originated using EEG Biofeedback for ADHD [Joel Lubar], did a diagnostic evaluation, called brain mapping, using the EEG equipment. During the break he asked me privately if I knew that my son was ADD and bipolar, with an addictive personality. Even though my father and my brother were bipolar, it had never crossed my mind that my son could possibly be bipolar. My father was diagnosed in his 50’s, my brother in his 40’s. I knew that he was ADD, and I had even put a second mortgage on our house to buy the EEG Biofeedbackequipment to treat him.

This had occurred because one day while I was home sick I turned on the TV, and just as the TV came on I heard someone say there was a new remedy for ADHD. I turned on to this particular station at exactly the beginning of a special about EEG Biofeedback. After we researched the procedure, we decided it was cheaper to purchase the equipment ourselves and train in the use of it than to spend six months in California having Nick treated. We were, however, having a difficult time stabilizing him with the Biofeedback equipment. We would use one protocol [C3beta] and he would slowly get better and then he would get worse. We would use another protocol [C4SMR] and he would slowly get better again and then again he would get worse. One protocol would reduce his impulsivity and eliminate his tics, but eventually he would become too relaxed. He would sleep too much: all night, after school, and during school. Using the other protocol would decrease his sleeping but eventually it decreased too much and he was sleeping only a few hours a night. As his sleep decreased his impulsivity returned. The workshop instructor, who used one protocol only for all of his clients, told us that EEG Biofeedback could not help Nick and that we would have to put him on medication.

My wife and I felt crushed. My father was one of the first people in the United States to go on lithium, almost 30 years ago. My father died last year. We were told that the toxicity of the lithium hastened his death. For the last 15 years before his death he had Parkinson-like tremors in both of his hands. We were told that the tremors were caused by the lithium. The tremors and the health problems my father developed from the medications were frightening. Eventually my father benefited greatly from the Biofeedback, but the damage had already been done. We were concerned about the long-term consequence of medications but felt Nick wasn’t going to make it to adulthood if we didn’t do something right away. We believed this impulsivity and risk-taking was life threatening. I called the company that sold the EEG Biofeedback equipment to us and they said they had recently developed a protocol for Bipolar Disorder. I was instructed to continue the two treatment protocols, but to do both of them within the same treatment session. We started treating him with the bipolar protocol in March, and hoped we could get him turned around by fall when he would be allowed to go back to school. Over the summer he seemed to improve. His impulsivity decreased. He became more cooperative. His affect and sleep improved. Nick went back to school in the fall, and he stayed out of trouble. He made new friends. His grades improved to A’s and B’s. The teachers liked him. He was voted the most improved student. My wife and I believe he could not have made it through school without EEG Biofeedback. If we had placed him on Ritalin, as the school was trying to force us to do, the stimulant would have aggravated his tics and precipitated even more serious emotional problems.”

Glen’s son Nick is now doing well as an adult. “Although my son has had problems maintaining a job, he has thrived socially. In addition to a long-term girlfriend (Sarah), he gets along well with friends and family who care about him. Nick enjoys his life and does well emotionally.” He is not on medications of any kind. Nick Traina, the son of Danielle Steel, committed suicide. He succeeded in this despite the fact that he was given 24-hour accompaniment. As a result of this tragedy, Danielle Steel established the Nicholas Traina Foundation to serve the needs of bipolar children. Unfortunately, the focus is predominantly on pharmacological approaches.

The other neurofeedback stories in Glen’s family should also be mentioned. His teenage daughter received neurofeedback for a health issue early in her high school career. Her scholastic GPA at the time was nominally 2.5. After the neurofeedback, her GPA quickly shot up to 4.0, and the daughter said that she really did not feel that she was working any harder. Her GPA has been 4.0 since that time, and this has now been sustained for all four years of college as well. The number of neurofeedback sessions were recalled as being in the range of thirty sessions.

Even more remarkable was the story of Glen’s father. He had suffered a gradual mental decline for some years, and ultimately was hospitalized with a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s. At that point, the father no longer recognized the home he had lived in for many years. His physician told Glen that his father would never be returning home, that he would have to receive continuing care from that time forward. If he left the hospital, it would be against medical advice. His father was under the impression that he was in Florida in a motel. He marveled at the good service that this particular motel was providing. He still recognized his son, but no longer recognized his wife.

“Who is this old woman in the house?”

“Do you think we can trust her?” he asked of Glen.

Glen did take his father out of the hospital, and it was against medical advice. He gave him some thirty sessions of neurofeedback. This allowed him to live at home. He once again recognized the house that he lived in, recognized his children, etc. He was able to live an independent life for another three years until his death, and surprisingly required no additional neurofeedback sessions over that time. One suspects that the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s may have been inappropriate. On the other hand, the dementia was unmistakable, as was the recovery therefrom.

After the father’s return home, he was given a mental status exam by his physician, a psychiatrist. The father could name the current president and other such facts. The psychiatrist was dumbfounded at the change he had observed. When told that neurofeedback had been the only intervention, he dismissed it haughtily. This is how ignorance protects itself.

The similarities between Nick Martin and Nick Traina:

Both children were named Nick.

Both would be of the same age.

The loves of their respective lives were named Sarah.

Both babies were large, requiring C-sections for their delivery.

Both were beautiful, happy infants.

Both started talking in complete sentences before age one.

Both were described as loving, charming, and sweet.

Both were seen as the class clown. There was no meanness in them.

Both had sibling that adored them

Both started going downhill in seventh grade.

Both declined significantly in their grades

Both showed significant increases in impulsivity as time went on

Both dyed their hair different colors, including in particular, green

Both found waking up and going to sleep becoming more of a power struggle.

Both wanted to stay up all night and sleep during the day

Both could get by with very little sleep

Both got to a point where they were no longer functional in school

Both sets of parents feared for their lives because of impulsivity.

This entry was posted on Thursday, February 24th, 2005 at 5:49 pm and is filed under Books and Literature. You can follow any responses to this entry through the RSS 2.0 feed. You can leave a response, or trackback from your own site.