The Crisis in Health Care

by Siegfried Othmer | July 29th, 2009 When health care was last dealt with in 1993, a reform proposal was sent to Congress that promised to restructure health care. But the existing interest groups managed to kill the proposal. Now that all of the stake holders are at the table in the latest effort to reform health care, it is guaranteed that nothing radically new will make its way into the final bill. Only incremental fixes will be tolerated, and only under condition that the existing interest groups will not be harmed. Yes, it is heart-warming that the AMA, big PhRMA, and the insurance industry are all on board with the reform effort, but that also means that the outcome will be well within their comfort zone.

When health care was last dealt with in 1993, a reform proposal was sent to Congress that promised to restructure health care. But the existing interest groups managed to kill the proposal. Now that all of the stake holders are at the table in the latest effort to reform health care, it is guaranteed that nothing radically new will make its way into the final bill. Only incremental fixes will be tolerated, and only under condition that the existing interest groups will not be harmed. Yes, it is heart-warming that the AMA, big PhRMA, and the insurance industry are all on board with the reform effort, but that also means that the outcome will be well within their comfort zone.

Even the proposal to complement the insurance-based system with a government plan is seen as a program-stopper. When it comes right down to it, the insurance companies really don’t want to compete against the government-run system, and it’s clearly not because governments can’t run health care. They are doing so everywhere else in the civilized world, and doing it more cheaply and better than we are. Our government is also doing it in Medicare, and it’s doing a darn good job of it under the current constraints. If the current insurance-based system is to remain the model, why don’t we ask, just for the sake of argument, what would happen if we have them take over education as well.

If access to health care is not a right in an advanced society, why should education be? Under the new regime, insurance companies would have to charge fees for access to education, and they would quickly determine how to cut their costs. Just as it is pointless to pay for traumatic brain injury or stroke rehabilitation ongoingly, it is pointless to continue to try to teach children who cannot learn. Out with special education. That will save a lot of money right there. And having learned about “brief therapy,” they would surely introduce the idea of “brief education,” in which children would be quickly graduated out of a program and left to learn the lessons of life elsewhere. We would have education provided by those who really don’t care whether children end up educated, just as they currently do not care whether we end up healthy.

This really gets to the crux of the matter. Insurance companies are not oriented toward the end result, which is health maintenance. Capitalism is lauded for being incentive-based, but when it comes to health care, the incentives are all skewed in the wrong direction. As private entities, insurance companies indeed do a better job than the government, but the job they are focused on is making money, not keeping people healthy. There is no way that this can ever converge on something that is aligned with the public interest. The only communal entity that is actually interested in the well-being of the public at large is the government. Hence only the government can assure that expenditures are aligned with societal goals. Some want to call this socialism, but of course it is not. The Post Office, the Police, the military, and the Highway Department are socialized, but not health care. In any system actually being thought about, health care delivery would still be by private parties. Government paid health care would be no more socialized than health insurance itself. All insurance involves the “socialization of risk,” and the same would be true, no more and no less, if the government dispenses the reimbursements rather than private insurance companies.

We do have an example of socialized medicine in this country, and it is the Veteran’s Administration and military hospitals. Members of Congress themselves have a chance to benefit from that system. The VA model does not give one a good feeling about government-run health care, or even about the proper incentives being in place. The scandal at Walter Reed Army Medical Center followed from a determined effort by the Bush Administration to down-play the problems of returning veterans. After the scandal broke, Donald Rumsfeld personally visited the Director and told him “to get this off the front pages,” which is different from actually solving the problem.

We are at a moment in our society where large private institutions are clearly in charge, and even government is subservient to them. So the traditional model of the government as the servant of the people no longer holds. All the rhetoric in the media is about costs, not about benefits. Health care is treated as if it were a black hole in the economy, a waste of resources. This follows from the fact that large institutions are the payers, and those who mainly provide the services are small private entities who don’t have access to the media. There is ongoing talk about whether too much is being spent on health care, while there is no such discussion about other items of social expenditure. Health care is going to be a key growth engine for our economy going forward, regardless of anything that may be done in the near term. In a morally neutral economic model, it does not matter much where growth comes from. And in a morally sentient appraisal, health care addresses the highest priority that people have in their lives. So what’s the beef?

In the bigger picture, we have reached the point where large institutions are no longer the engines of innovation, but rather the custodians of the status quo. This is true across the board, not only in health care, and it has profound implications for our national future. In the field of health care, the most serious impact follows from the fact that Big PhRMA has captured both the universities and the National Institutes of Health, so that innovation is restricted to its narrow field of interest. This is, of course, the principal reason why neurofeedback remains invisible within the NIH. It represents a looming threat to drug industry hegemony.

Fixing Health Care

The fundamental problem in health care is that service delivery is not matched well to the problems at hand. We offer specialized and atomized solutions to what are likely much more systemic problems. An integrative perspective on the patient is lacking, as is an integrative medical discipline. The system is rigidly diagnosis- and procedure-based, and remains frozen in place because of the nature of insurance-based health care. This system has the infernal tendency to put every professional in a strait jacket with respect to what they may do, so the over-all care for the patient suffers. At every point in the chain of events, care givers must align their thinking with what the insurance realm allows them to do.

A systems perspective is needed, and the framework for such a perspective is furnished by the network model currently emerging in the neurosciences. The systems perspective orients us toward the ongoing quality of functioning rather than the ultimate breakdown of the system, where remedies are no longer availing. This amounts to a prevention strategy, which is what is needed, but the payoff is not mere prevention of dysfunction and disease but rather better function all along the way. The education model is relevant here. Free education can be seen, rather darkly, as society’s means of containing societal dysfunction—crime and dissolution. An emphasis on early optimization of brain function will similarly avoid large health expenditures on remediation later.

I may have referred in an earlier piece to a long-term study of Harvard students in which it was found that physical health late in life was strongly correlated with emotional status during their student years. Emotional well-being can be taken as an index to brain functional status. A study of blacks in the Los Angeles area found that the strongest predictor of long-term health outcome was socio-economic status. This factor was larger than any of the usual risk factors: obesity, smoking, drinking, divorce, violence, etc. In fact, it was larger than all of them put together. At the other end of the socio-economic scale we know that health status correlates nicely as well. Socio-economic status is an index to the quality of brain function at both ends of the scale, and of course emotional status plays into this as well.

A Systems Perspective

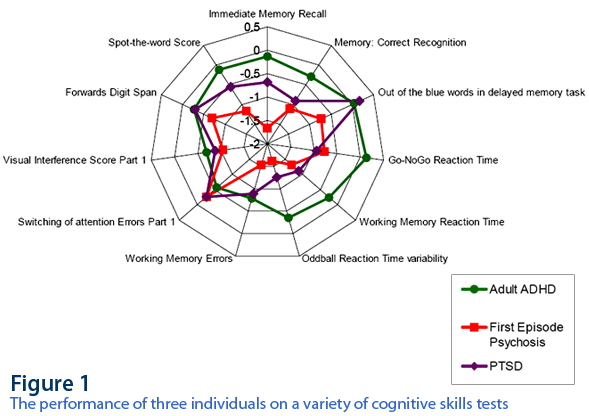

The fact that we are dealing with systems-level problems is illustrated nicely with a report given by Evian Gordon, of the Brain Resource Company, at the neurophysiology conference in Nijmegen, Holland, in 2007. In Figure 1, we see the performance of three individuals on a variety of cognitive skills tests. The response of an ADHD adult is shown in green. The response of a person with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder is shown in purple. And the response of a person after a first psychotic episode is shown in red. In each case, the dysfunction is global, and not restricted to narrow functional domains.

We now have a remedy for this more global kind of brain dysfunction in neurofeedback, and the evidence in favor of this proposition continues to mount. At the same time, Blue Cross is cutting back on coverage for biofeedback. This cannot be happening because of adverse findings with regard to biofeedback because the trend is the other way. It must be happening because biofeedback and neurofeedback are being billed more frequently, and this is beginning to bite into the bottom line. The response of the cold-blooded leeches in the corner office is to cut off this new drain on their resources. Surely no one there is asking the question as to whether this new popularity of biofeedback might have a solid foundation in the clinical world because we are actually solving real problems.

So we can just forget the insurance companies as an element of the necessary innovation strategy that must occur in medicine. We turn instead back to the education model. If free education is an entitlement in a civilized, developed society, then a technique that enhances our societal return on that investment should be also. It is in our collective self-interest. We should provide every child the opportunity to improve his or her brain function by direct training, and we will see ongoing benefit not only in school performance but in all of the subsequent health history of the child. The means of cost reduction in health care is entirely in our hands already.

Over the longer term, this will mean reduced utilization of expensive care facilities. But providing the new brain-training services will demand large resources in terms of manpower. This will build the real economy; this will provide real growth in employment; and this will abort the waste of resources currently expended in frantic, pointless health care delivery near the end of life. When all is said and done, the top quintile in terms of health status among Americans matches up with the bottom quintile in England. There could not be a more damning and succinct indictment of our system of health care delivery than this. And on top of that, we are paying twice as much as the British are for health care. The remedy that will leap-frog even British health care is at hand in the broad and ultimately universal deployment of neurofeedback.

Interesting points of view, Mr. Othmer, I agree in most of the points. This is the right time to discuss these important social issues that affect everyone. Remember also that the path that takes the US in this regard affects the approach taken in the rest of the world.

The reason why, until now, self regulation techniques and science (including biofeedback), and preventive natural treatments are not mainstream, correlates directly with the powerful lobby of certain interests groups at academic, media and government levels. That is heavily affecting not only the world’s population health, but is also related to deep social problems that are only going to be overcomed once that the public mental health systems start to deal with the root causes. A similar discussion to this one was done in the UK’s parliament, very well documented and exposed in the document “Influence of Pharma Industry UK – HOC Com.pdf”, searchable in the internet.

Secondly, I agree that neurofeedback should be a major part of a cost effective and safe educational/healthcare reform. The benefits that you mention are scientifically proven at this point. As you say, biofeedback should go mainstream now.

The fact that biofeedback and other safe, natural, cost effective treatments aren’t taken seriously for the healthcare can be fixed, but there has to be created a social and political force that can be strong enough to be present (represented) in the negotiations table when dealing with each government in the world. That has never existed. But that can change. It depends on the capacity of people like you and other prominent leaders to get together and do something. I am thinking in leaders of the psychological communities (like Daniel Goleman), of well known social scientists (like those of the OLPC or the ones from the open source movement), others worried about the natural approaches to social problems (likewise the green movement), and those related to hollistic approaches (like Deepak Chopra). Alone you are not going to be read but by only a few visitors to your blog, like me. But if you join forces you can raise the attention of the public and put some legitimate demands on the negotiations table. Like serious research and development funding resources for cost effective, natural and/or safe health approaches, and support of a preventive public education on the media, like the one that is already existent in the UK.

If leaders of similar groups to those mentioned join forces this situation can change. Look at what happened with the automotive and petrol industry during the last 100 years. They managed to lobby and control the political powers and scientific communities so that almost no research or investment was done in the electric cars or clean energies, with the sad consequences to the planet and the economy known by everyone. But at least after all, the people organized to do the right things and now, for the first year in history, the US is taking serious action towards supporting a sustainable action in this regard. The people finally woke up and chose this president so that he could do it. Similar stories can be told about the cigarrette and nuclear weapons industries.

The situation you are talking about can change, but it is required a bigger organised action to inform the public and create consciousness, as well as a concrete set of proposals that can work in an effective way for creating human development. That’s how democracy must work. You people may not have the money and media coverage that pharma industries have, but there is a big amount of creative people that share certain core values, and that have a lot of important things to say and do.

Thanks for your thoughts. We’ll probably remain in the viral growth mode for a while yet, and the insularity of this field will likely remain an impediment for some time to come. It’s not something that we can readily influence ourselves except incrementally. To a large extent the “connectivity” between like-minded initiatives will emerge because of factors operating independently in a large number of places. It’s going to take time, I have to keep reminding myself. One cannot produce a bottom-up revolution with a top-down strategy.

Just as I am making the case for a shift toward a prevention strategy based on a systems-level understanding of our biology, it turns out that a bill making its way through Congress to reduce breast cancer incidence in women is meeting with opposition. Stephen Woloshin and Lisa Schwartz, authors of the book “Know your Chances; Understanding Health Statistics,†argue that what is being proposed is a waste of time and money, and may do more harm than good through the adverse impact of “false positives in medical exams.†First of all, they argue, the prevention strategy targets women before the time where there is any significant risk of breast cancer. And second, “there are no proven strategies†for reducing breast cancer incidence in any event.

First of all, a prevention strategy should be put in place well before breast cancer seriously becomes an issue. And secondly, just because there is no specific counter-measure does not mean that a general promotion of anti-cancer lifestyles might not be useful. The burden of proof for such general strategies should be a lot lower than for discrete medical procedures. If we waited for proof of efficacy, we’d be waiting for a generation for answers. In their criticism, the authors also reflect their bias toward an exclusively medical perspective on this issue.

It is not too early for a fifteen-year-old girl to become aware that psychological trauma is a risk factor for a variety of physical disorders late in life. If she ever becomes the victim of sexual aggression, for example, this should be a health priority for her beyond most others. Psychological health in general is the factor over which we are in a position now to exercise the greatest degree of control.

A similar controversy is arising now with respect to Alzheimer’s. Should genetic screening be recommended to identify elevated risk of Alzheimer’s? No, it is argued, since we don’t have an effective treatment in any event. But it is now known that by the time symptoms become noticeable the disease process has been underway for some years already. The same is true of Parkinson’s. If a brain-training strategy can postpone the threshold of onset of symptoms, should this strategy not be instituted earlier rather than later, for whatever that may be worth?

We should not insist on gold-standard evidence for this approach before instituting it. We should instead track outcomes for post-analysis. The costs of such brain-training should be balanced off against the ongoing benefits of improved cognitive function, sleep, and mood regulation, etc. The costs should not be balanced off against an uncertain and as yet unquantifiable benefit for the incipient Alzheimer’s condition.

People are fearful that government will take away their freedom of choice in their healthcare. What they do not realize, is the great delusion that health care companies have created that they actually have freedom. Today the decisions are made by private companies about individual health and in the aggregate about our healthcare policy. In the media campaign only these two choices are presented choice as it is or government control There needs to be a third choice at the table, and that is, return decisions to the healthcare provider, period.