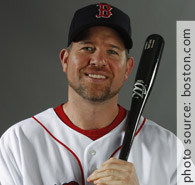

Sean Casey’s Neurofeedback Story

by Siegfried Othmer | December 16th, 2009 For a number of years now I have been hearing from Leslie Coates in Florida about his work with a top-rated hitter in baseball. For reasons of client confidentiality, I never had a name to go with the story. When reporters would ask us about sports applications, the best story of all had to remain somewhat amorphous. At this year’s ISNR Conference the audience got to hear about the training directly from the person involved, Sean Casey, in a joint presentation with Leslie Coates and Wes Sime.

For a number of years now I have been hearing from Leslie Coates in Florida about his work with a top-rated hitter in baseball. For reasons of client confidentiality, I never had a name to go with the story. When reporters would ask us about sports applications, the best story of all had to remain somewhat amorphous. At this year’s ISNR Conference the audience got to hear about the training directly from the person involved, Sean Casey, in a joint presentation with Leslie Coates and Wes Sime.

Sean Casey started out auspiciously in baseball, with a batting average of 0.461 in college at the University of Richmond. He was drafted into the Major Leagues by the Cincinnati Reds ten years ago, and soon after a promising start he was hit in the face by a ball he wasn’t expecting. The bones around the eye socket were broken, and although he tried to keep playing, his batting average hit bottom: 0/30. He was sent back to the minors, where he connected with sports psychologist Wes Sime, with whom he worked for two years.

Eventually Wes suggested EEG biofeedback, and referred Sean to Leslie Coates in Florida. He trained intensively with Leslie, and that was the start of a long-term relationship. At first Sean was put off by the whole idea of neurofeedback, but he had the assurances of Wes Sime to fall back on, and he persevered. Down the line he encountered a second discouraging aspect of the training. He was bombing the TOVA Continuous Performance Test. It turns out that he was beating the 200msec threshold for anticipatory responses fairly routinely. This was ruining his scores, until it was noticed that the responses were usually correct—they were just consistently very fast. (Some years ago, this same phenomenon was no doubt in play when a British sprinter was knocked out of the Olympics for “beating the gun” twice in a row. He had been practicing his starts for years, and probably was simply faster than the Olympic officials had allowed for. Barry Sterman encountered the same phenomenon in testing B2 pilots with a CPT.)

Back with the Reds, Sean was on the way to a lifetime batting average of 0.302, and the 7th best all-time fielding percentage for a first baseman. He was a three-time All-Star. His best year with the Reds was 1999, with a 0.332 batting average, 25 HRs and 99 RBIs. Traded to Detroit, he had a 0.432 batting average in the 2007 World Series while garnering two home runs. Then he was with the Boston Red Sox before his recent retirement. He was also voted “The Nicest Guy in Baseball” by his peers.

In 2003 he injured his groin, but continued to play the remaining two months of the season. When he couldn’t get out of bed one day after the season was over, a broken pelvic bone was diagnosed, and he was ordered to rest for the entire four months of the off-season. This gave him the opportunity for intensive neurofeedback, and that is also when the Interactive Metronome was introduced into the regimen. He found success with the IM to be tremendously satisfying: “I love that cow bell.”

Sean credits his success in hitting to the combination of neurofeedback and the Interactive Metronome. Sean’s willingness now to discuss his experience may very well lead to greater acceptance of neurofeedback among his peers. Here we have a good example of the non-clinical use of neurofeedback that can allow the technique to marble into the society without the downside of association with mental failings, disorders, disabilities, and assorted shortcomings.

It is significant that despite his various injuries, Sean never defined himself in terms of those injuries, but rather continued to see himself as potentially the best hitter in baseball. The tendency to see oneself in positive terms is actually fairly commonplace, and this no doubt accounts for the reluctance of people to seek help for their dysfunctions. We see this not only in top sports people who have every reason to think well of themselves, but quite generally across the spectrum.

We can expect that a pitch to enhance function might be a lot more appealing to people than the offer to banish their dysfunctions. This might even work if it were not for the large commitment of funds required to undertake neurofeedback. Somehow we have to find a way to ease the path of entry for people who regard themselves as entirely functional, and who are not facing a crisis of some kind. That calls for some innovation on the service delivery side, particularly in the current economic environment.

Enhancing function for people who do not see themselves as injured/disordered, etc. appears to be an excellent approach, and one which will ease decision-making for persons who do have disorders as it de-stigmatizes this approach to improving brain self-regulation. It also broadens the population to which it can have appeal and makes it a more attractive treatment modality for practitioners. Also, I really like it!! I am still hoping to be able to take the training and find a way to become a practitioner.

Let me give you all the encouragement I can. The field of health care is growing throughout the recession. Within the larger health care field the neurosciences are the growth industry. Within the neurosciences the frontier in terms of actual practice lies with neurofeedback. And within the field of neurofeedback, our own approach appears to be the most effective as well as the most time-efficient.

question:

I know certain regions of the brain have been identified as areas of the brain which are responsible for Emotional intelligence.

Is it possible that Neurofeedback can be used to strengthen ones Emotional intelligence by teaching us to use these parts of our brain more effectivley.

In a word, yes. We are this year observing the 20th anniversary of the first study to show major increases in IQ scores in minimally neurologically impaired children with neurofeedback. This was followed up two years later by a study we did which confirmed those results. Now we know that the ability to improve IQ scores is also available to us through neurofeedback for emotional intelligence. The difference, however, is that the gains are not as readily quantifiable as they are for the cognitive skills which are assessed in standard IQ tests. On the other hand, the effects of the training for emotional competence are much more readily observable. A person’s capacity for intellectual functioning is not so obvious. It needs to be tested for. Shortcomings in the domain of emotional regulation, on the other hand, are much more obvious. So the changes we observe are very persuasive, even though they may not be readily quantifiable.